Mapping Herstory

Who were the women who shaped our streets in HK?

Street names do more than guide us—they shape a city’s story and reveal its values. Consider Hong Kong. Out of more than 330 streets named after individuals, only 27 (just 7.9%) honour women. Even among these few, only two recognise Chinese women, and they are mostly remembered as wives of famous men. Merely one street celebrates a woman for her own achievements, a clear reminder of how colonial legacies and a patriarchal mindset continue to obscure local contributions.

Yet Hong Kong is not an isolated case. A study by the European Data Journalism Network examined 145,933 streets across 30 major European cities and found that 91% of them commemorate men. A closer look at 5,000 street names in Paris, Vienna, London, and New York shows similar imbalances:

Paris: Only 4% of street names honour women, reflecting a legacy of 1860s-era figures—artists, writers, scientists, and military leaders—tied to Napoleon III’s grand transformation of the city.

Vienna: In a surprising contrast, 54% of streets are named after women, particularly early 1900s artists and social influencers, though 45% of these honours go to foreigners.

London: About 40% of street names celebrate women, largely featuring royals, politicians, and military figures from the 1700s and 1800s during the city’s post–Great Fire renaissance.

New York: With only 26% female-named streets, the city primarily honours business leaders, civil servants, and 9/11 heroes—firefighters, EMTs, and others—with a scant 3.2% recognising foreigners.

These figures invite us to reflect on whose stories our streets tell. What does it truly mean for a city to honour women through its street names? As we explore this topic, let’s reconsider our urban landscapes and ask: Who are the women we celebrate—and who are we leaving out?

This shows a map of streets named after people in Hong Kong. Streets highlighted in purple are named after women, while those in green are named after men.

Royals

Queen Victoria (1819 - 1901)

Queen Victoria: The City’s Early Namesake

At the heart of Hong Kong’s royal legacy is Queen Victoria. Reigning from 1837 to 1901, she led Britain during a transformative period marked by the height of the British Empire. Her influence extended into various realms, including politics, culture, and social reform, and her reign is often associated with the expansion of British colonialism across the globe.

During her reign, Hong Kong was ceded to Britain after the First Opium War in 1842, establishing it as a crucial outpost for trade and military strategy in Asia. Once known as the “City of Victoria” during its era as a British Crown Colony, Queen Victoria is remembered on nine streets across Hong Kong.

A Living History Along Queen’s Road

One of the city’s oldest and most iconic avenues is Queen’s Road. Stretching from Shek Tong Tsui to Wan Chai, this road is divided into four sections: Queen’s Road West (皇后大道西), Queen’s Road Central (皇后大道中), Queensway (金鐘道), and Queen’s Road East (皇后大道東). The construction of Queen's Road started in May 1841, only four months after the British landed on the Island. Originally called Main Street, it was renamed in March 1842 as a tribute to Queen Victoria—even though a translation error initially rendered her title as “queen consort” (皇后) rather than “sovereign queen” (女皇).

Built along the beach by Royal Engineers and 300 laborers from Kowloon, Queen’s Road began at the very spot where Sir Henry Pottinger, Hong Kong’s first governor, set up camp in 1842. Over time, as the city expanded under British rule, this street transformed into Hong Kong’s bustling main artery. It wound past upscale clubs, humble squatter areas, military barracks, and taverns. Early governors built their homes here, and the street soon became home to the first post office and several Christian churches. Today, landmarks like HSBC at 1 Queen’s Road Central continue to uphold its storied legacy.

A painting of Queen's Road Central in 1865 (source: wiki)

Streets Celebrating the Royal Jubilee

Nearby, Queen Victoria Street (域多利皇后街) and Jubilee Street (租庇利街) interlace through Central Hong Kong, stretching about 200 meters. Originally laid out around 1875 to link Queen’s Road Central with Des Voeux Road during early reclamation projects, they were renamed in 1887 for Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee. By 1898, further reclamation extended these streets to Connaught Road.

In the late 19th century, Queen Victoria Street became a bustling hub for traders and seafarers. It offered Western goods ranging from butter and jam to canned food and cigarettes, with shops lining the waterfront and drawing customers straight from Victoria Harbour. The opening of the Jubilee Street Pier in 1919 and the Vehicular Ferry Pier in 1933 transformed the area into a key transport gateway—a role it maintained until the ferry service closed in 1994.

A Scenic Tribute on Victoria Road

Victoria Road (域多利道), running along the western tip of Hong Kong Island, connects Kennedy Town to Pok Fu Lam. Its construction began in June 1897 to mark Queen Victoria’s 60th anniversary, and it was originally named Victoria Jubilee Road (域多利慶典道). Governor Sir Robinson laid the foundation stone amid a time capsule containing newspapers, banknotes, and coins.

By the 1910s, the road was expanded and renamed, evolving into one of Hong Kong’s most scenic drives by the 1920s—just behind the celebrated route to The Peak. What started as a muddy track leading to the Chinese cemetery at Kellett Bay was transformed into a concrete road in the 1960s to support the development of Wah Fu Estate. During Queen Elizabeth II’s Silver Jubilee in 1977, a new time capsule was added, enhancing the road’s role as a living monument to royal milestones.

Colonial Hotel on Jubilee Street in 1900s (source: gwulo)

Victoria Jubilee Road in 1903 (source: gwulo)

A new time capsule, dedicated to Queen Elizabeth II's Silver Jubilee, is being placed in the base of the Victoria Road Memorial in 1977 (source: Getty)

Other Layers of Urban History

Not every street’s story is straightforward. Consider Queen Street (皇后街), originally known as Wo Hing West Street (和興西街), which once ended at Wing Lok Pier. As the city grew, Queen Street merged with Connaught Road West and Des Voeux Road West to form a triangular intersection that locals came to call Triangle Pier.

Then there’s the story of Victoria Park Road (維園道). What is now an urban road was once a safe haven—a typhoon shelter where small fishing boats in Causeway Bay found refuge. In the 1950s, as the city expanded, the bay was filled in, the shoreline shifted north, and the government set out to reclaim the land for public use. The result was Victoria Park, a vibrant green space that opened in 1957, while a new typhoon shelter was built just north of the park.

A key feature of Victoria Park is the restored Queen Victoria statue. Originally cast in Pimlico, London, the statue first stood proudly at the centre of Statue Square in Central, unveiled on Queen Victoria’s 77th birthday in 1896. During the Japanese occupation, however, it was removed and almost melted down along with other statues. After the war, Queen Victoria's statue was rescued and restored in 1952, finally finding a permanent home in Victoria Park.

Queen Victoria's Statue in its original site in Central, 1896 (source: gwulo)

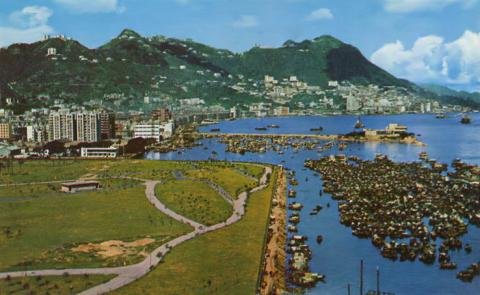

The newly built Victoria Park in 1958 (source: gwulo)

The Windsor Sisters: A Tale of Two Royals

Princess Margaret visiting Choi Hung Estate in 1966. (source: Housing Authority)

Interestingly, Hong Kong celebrated Princess Margaret with a road name long before her better-known elder sister, Queen Elizabeth II. Born in 1930, Princess Margaret charmed visitors with her vibrant personality and glamorous style. During her March 1966 visit—a key stop on a Far East tour aimed at strengthening ties with Britain’s overseas territories—the city was captivated by her appeal. An extension of Nairn Road (楠道) on the Kowloon Peninsula was completed just in time, and the new section was renamed Princess Margaret Road (公主道).

Queen Elizabeth II, born in 1926 and reigning for 70 years through eras of transformation and decolonisation until her passing in 2022, made her mark during two visits—in May 1975 and October 1986. Her enduring influence appears not only in street names but also in the renaming of landmarks. The New Kowloon Hospital, once the largest general hospital in the British Commonwealth when it opened in 1963, was renamed Queen Elizabeth Hospital. In 2008, two roads on the hospital campus were dedicated as Queen Elizabeth Hospital Road (伊利沙伯醫院路) and Queen Elizabeth Hospital Path (伊利沙伯醫院徑)—the only streets directly referencing her.

Additionally, funds from the public’s wedding gift fund and support from the Hong Kong Jockey Club in 1947 helped create the Queen Elizabeth II Youth Playground. Completed a year after her ascension to the throne in 1952, it was the first indoor gymnasium in Kowloon and the most advanced in Asia. The venue was eventually demolished in late October 2008 and rebuilt as the current MacPherson Stadium.

The Queen visiting a market in 1975 (source: SCMP)

Queen Elizabeth II Youth Playground in 1953 (source: Macpherson Stadium)

Significant Others

In Hong Kong, about one-third of the streets named after women do so not because of their own public achievements but as a nod to their roles as wives or daughters of influential figures. These names serve as quiet reminders of an era when a woman’s identity was defined by her connections to power, be it colonial governors, missionaries, businessmen, or politicians.

Lady Clementi and her husband on the left at a wedding party in grounds of Government House in 1926 (source: Gwulo)

Lady Clementi: Romantic Horseback Rides

On the southern side of Hong Kong Island, Section 4 of the Hong Kong Trail unfolds a romantic slice of history. In 1929, Hong Kong’s 17th Governor, Cecil Clementi—renowned for his fluency in Cantonese and progressive reforms—decided to transform an old horse route from Wan Chai Gap to Wong Nai Chung Gap into a public mountain trail.

In a heartfelt tribute, he requested that the trail be named in honour of his wife, Marie Penelope Rose Eyres, giving birth to Lady Clementi’s Horseback Riding Trail (金夫人徑). Later, the Works Department extended this legacy with Sir Cecil’s Ride (金督馳馬徑), connecting Wong Nai Chung Gap to Mount Parker Road. More than just a path, these trails evoke memories of a couple who raised four children and forged countless adventures on horseback. Lady Clementi’s life spanned continents, she passed away in 1970 in Wycombe, Buckinghamshire, leaving behind a legacy etched into the very trails of Hong Kong.

The Whitener couple at their HK farewell party in 1957 (source: Legacy.com)

Barbara Whitener: Quiet Legacy in Po Lam

Over in Tseung Kwan O, the story of Barbara Whitener reveals a quieter legacy. Born in South Carolina in 1923, Barbara married Sterling Whitener, and together they served as missionaries in Hong Kong from the early 1950s until 1967, raising six children along the way. When Sterling co-founded the Haven of Hope Tuberculosis Sanatorium in 1955 (now the Haven of Hope Hospital), a road was built to help transport patients and supplies. This road was named after Barbara’s maiden name, rendered in Chinese as Po Lam Road.

As the area grew into a vibrant district—with Po Lam Road (寶琳路), Po Lam Road North (寶琳北路), Po Lam Road South (寶琳南路), and Po Lam Lane (寶琳里)—the Whitener name became etched into the urban landscape. Barbara passed away on March 28, 2023, just before her 100th birthday, leaving us to wonder if she ever strolled along the streets that now proudly bear her family name.

The Lee Family, with Wong Lan Fong on the second right (source: Facebook - Business Tales of Hong Kong)

Wong Lan-fong: A Pillar of Strength

The story of Lan Fong Road (蘭芳道) stands out as one of remarkable resilience. Born on June 3, 1880, Wong Lan-Fong became the first wife of Lee Hysan, a businessman whose early career was connected to the opium trade. She was the first Chinese woman, and the only one, to have a street entirely dedicated to her name.

In 1924, Lee Hysan purchased land in East Point from Jardine Matheson for HK$3.8 million, initially planning to build an opium refinery. After the government banned opium, he pivoted to develop Lee Garden Hill instead. He named several streets after his ancestral Guangzhou and notable individuals, including Kai Chiu Road (啟超道), honouring reform-minded intellectual Leung Kai Chiu and his wife, Wong Lan-fong, an illiterate woman from Toishan with bound feet.

When Lee was assassinated in 1928, Wong was left to care for his extensive family. With unwavering resolve, she managed not only her own children but also those born to his concubines. Working alongside her 23-year-old stepson, Richard Lee, she navigated legal battles, settled steep taxes, and even relocated the family during World War II for safety—later returning to rebuild their waning business empire. Her determined efforts eventually laid the foundation for Hysan Development Co., Ltd., which went public in 1981 and continues to shape Hong Kong’s skyline today. Her name commemorated on a street honours not just a wife, but a true pillar of strength and perseverance.

The Soares Family with Julia on the right and Emma in the middle (source: Friday Everyday)

Emma and Julia Soares: Cosmopolitan Family

In Kowloon, the legacy of a visionary developer also echoes through family names. Francisco Paulo de Vasconcelos Soares—often called the “Father of Ho Man Tin”—envisioned a neighborhood that blended nature with modern life, drawing inspiration from Ebenezer Howard’s Garden City concept. As he laid down the framework for his self-sufficient community in the early 1920s, he chose names that evoked hope and renewal: Victory, Peace, and Liberty adorned the streets. But his most personal tributes were reserved for his family. Soares Avenue (梭椏道) honoured his father, who designed S. Francisco Garden in Macau, while Emma Avenue (艷馬道) and Julia Avenue (棗梨雅道) commemorated his wife and daughter.

Emma, born in 1871 into a prominent Portuguese family (her father was one of the founding shareholders of HSBC) in Hong Kong, married Francisco in 1901. Their daughter Julia, born in 1904, later married Charlie Correa, an auditor at Jardine Engineering. The couple moved to Shanghai’s French Concession where they welcomed two sons. After three years, family ties drew them back to Hong Kong, where Charlie joined an American broking firm and the Correa clan settled into a grand mansion on Liberty Avenue. Their names, etched into the urban fabric, tell a story of a cosmopolitan legacy that bridges cultures and generations.

Ng Mui Chu: Half a Street

Ng Mui Chu with a girl scout (source: Yan Oi Tong)

In 1963, the Street Name Selection Committee established guidelines to avoid naming streets after living individuals. However, an exception was made for Lau Wong-fat (劉皇發), known as the "King of the New Territories," who served as chairman of Heung Yee Kuk for 35 years and held various public offices, including as a member of the Legislative and Executive Councils. In 1986, Wong Chu Road (皇珠路) was named to honour both Lau Wong-fat and the homophone of his wife’s name, Ng Mui Chu (吳妹珠), marking a rare acknowledgment of a living person in the city’s street naming history.

Married for over 60 years, Mui Chu built her own reputation in the 1990s by leading the Tuen Mun Girl Scouts, supervising both Yan Oi Tong Kindergarten and Yan Oi Tong Madam Lau Wong Fat Primary School, managing Yan Oi Tong for four terms, and serving as honourary president of the Yin Ngai Society—making her the only living person to be commemorated with half a street name while celebrating her lifelong dedication to community service.

Deities

Tin Hau Temple with Kwun Yum Statue in Repulse Bay (source: blue balu)

Across the globe, many cities weave spirituality into their very streets. A survey of 32 European cities reveals that the Virgin Mary appears on 369 street names in 26 cities, while Saint Anne, her mother, graces 37 streets in 20 cities. These numbers show how deeply our cultural and spiritual values are built into urban life.

In Hong Kong, this spiritual touch remains strong. Kwun Yum (觀音), the Bodhisattva of Compassion, is a constant source of comfort for many. Her gentle influence is evident on streets like Kwun Yam Wan Road (觀音灣路) and Kun Yam Street (觀音街), where her presence serves as a daily reminder of kindness and mercy.

Equally beloved is Tin Hau (天后), the Sea Goddess. With roots in Hong Kong’s humble fishing village past, Tin Hau is celebrated as the guardian of fishermen and seafarers. Over 80 temples across the city honour her, preserving legends of a mortal woman from the Song Dynasty of Fujian who was so gifted in predicting weather that she ascended to immortality at just 29. Today, her legacy lights up the urban landscape—from Tin Hau Temple Road (天后廟道) to Tin Hau Road (天后路) and even an MTR station.

Merit

Florence Nightingale - ‘The Lady with the Lamp’ (source: wiki)

In Hong Kong, just one street uniquely celebrates a woman for her individual achievements: Nightingale Road (南丁格爾路). Established in 2008, alongside Queen Elizabeth Hospital Road and Queen Elizabeth Hospital Path, this street is significant as it marks the first time since Hong Kong’s 1997 handover that a street has commemorated a foreign figure. More importantly, it celebrates Florence Nightingale not simply as a figure connected to power but as a visionary in her own right.

Florence Nightingale was much more than a pioneering nurse. Born in early-19th-century Florence to a wealthy British family, she defied societal expectations to dedicate her life to those in need. During the Crimean War, her insistence on strict sanitation practices in military hospitals saved countless lives, fundamentally transforming medical care on the battlefield.

Her influence, however, extended well beyond the war zone. At a time when numbers were often met with skepticism, she used data visualisations and statistics to highlight the urgent need for hospital reforms. Her clear and compelling presentations not only garnered public support but also redefined the future of patient care, elevating nursing from a mere duty to a respected profession. As someone who loves data visualisations and their power to tell impactful stories, I find Nightingale's legacy particularly inspiring and I am glad she has her own street in Hong Kong!

One of Nightingale’s many data visualisations (source: Scientific American)

Map showing ‘Caroline Hill’ in 1875 (source: Internet Archive)

The Big C Theory

Yet not every street name comes with a story as straightforward as Nightingale’s. Caroline Hill, first appearing on Hong Kong maps in 1873, remains shrouded in mystery. Despite spending hours on colonial records and the annals of early governors’ families, no trace of a Caroline in that context has emerged. So, who was Caroline?

My theory is that the hill may honour Caroline Fischer—the wife of Maximilian Fischer, a long-established China hand who became the P&O agent in Canton in 1850 and, by 1855, the commander in Hong Kong. Caroline passed away in 1859, yet her legacy endures alongside her husband in their large chest tombs at Hong Kong Cemetery. The intriguing mystery of Caroline Hill Road (加路連山道) remains an open chapter in Hong Kong’s history. If anyone has clues or theories about who Caroline might have been, I’d love to hear your insights!

The Legend of the Seven Sisters

Seven Sisters Bay in 1920s (Source: Our China Story)

Tsat Tsz Mui Road 七姊妹道 (Seven Sisters Road) is one of North Point's most well-known streets with a memorable name and eerie urban legend around the Seven Sisters. So, who were the Seven Sisters?

According to local legend, seven women—the "self-combed" sisters—vowed never to marry, choosing instead to define their own destiny. When the third sister was forced into an arranged marriage, she refused to surrender her autonomy. In an act of defiant unity, all seven vowed to "live and die on the same year, month, and day." Legend had it that they clasped hands and leaped into the sea, their forms forever enshrined as seven rocks along the shoreline of Seven Sisters Bay. Though modern land reclamation has erased these stones from view, and the bay itself has been transformed into a popular swimming area, the stones set the stage for an athlete who carried that spirit into history.

In the early 20th century, swimming became popular in Hong Kong, and the Seven Sisters reclamation area, accessible by tram, became a favored swimming spot. Various organizations built swimming sheds there, including the Chinese Recreation Club and the South China Athletic Association. It was here that, long before the era of Hong Kong’s celebrated Olympian Siobhán Haughey, a pioneering athlete named Yeung Sau-King (楊秀瓊), affectionately dubbed the "Flying Fish," made her mark.

A special feature on Yeung in the bilingual ‘Illustrated Weekend News’ magazine published in Shanghai in 1935 (source)

Yeung Sau-King: Pioneering Athlete

Born in 1918 in Hong Kong, she had already clinched the title at the Victoria Harbour Cross-Harbour Swimming Championship by the tender age of twelve. Her meteoric rise continued as she triumphed at the 1933 National Games in Nanjing and outpaced stiff competition at the Far Eastern Championship Games, securing gold medals against athletes from Japan, the Philippines, and India.

In 1936, Yeung Sau-King broke new ground by becoming the first woman to represent China at the Berlin Olympics in swimming—setting a national record in the 100m backstroke while inspiring countless young women. Even as the outbreak of World War II disrupted her athletic career, her indomitable spirit led her to serve as an intelligence agent during the Japanese occupation. After the war, she channeled her determination into journalism, community service, and lifesaving advocacy. Appointed as the founding chairwoman of the Hong Kong Life Saving Society’s Women’s Department in 1962, she steered the organisation through challenging times, ultimately earning the prestigious Medal of Merit in 1968 from the Commonwealth Headquarters.

Yeung Sau-King’s multifaceted legacy—as an athlete, patriot, journalist, and community leader—mirrors the enduring strengths symbolised by the Seven Sisters. Throughout history and myth, women have played a substantial role in defining Hong Kong's identity.

Name That Woman

Exploring Hong Kong's street names—from the familiar ring of Queen Victoria to the quieter note of Tsat Tsz Mui Road—we see much more than just names on a map. These streets carry the stories of women who showed strength and heart. Yet, even as we celebrate these names, it feels like many local voices are missing.

Think about the everyday women who shape our city:

Teachers who spark curiosity and learning every day.

Community leaders who build strong, caring neighborhoods.

Artists and cultural figures who brighten our lives with creativity and passion.

Their contributions might be quiet, but they have a lasting impact on Hong Kong. So, we ask: Which local heroines, with their everyday courage and hard work, deserve to have their names celebrated on our streets? Imagine a future where every street honours the many diverse contributions of Hong Kong’s women—both the famous ones and those rarely recognised.

By looking at our city’s layout with fresh eyes and honouring these local contributions, we can create a map that tells a fuller, more honest story of Hong Kong—a story where every name reflects the strength and diversity of its people.