Joy Luck Club

The Cartography of Wishful Thinking

Source: Xiaohongshu

On an ordinary afternoon tourists gather beneath the sign for Fife Street (快富街, Quick Affluence Street). They pose and post the shot to Xiaohongshu. While it looks like a casual holiday snapshot, the gesture taps into a deeper urban tradition: in Hong Kong, Chinese street names function as civic incantations, codes designed to summon fortune and etch collective desires into the pavement.

The city’s dual naming system is a relic of the colonial era. English names were typically administrative or commemorative, honouring governors, forgotten battles, or distant British locales. Their Chinese counterparts, however, were often expressive and intentional, embedding hopes for prosperity, longevity, and harmony into the daily commute. Where the English name represented the machinery of empire, the Chinese translation offered a promise of luck or a shield against misfortune.

Good Luck, Babe!

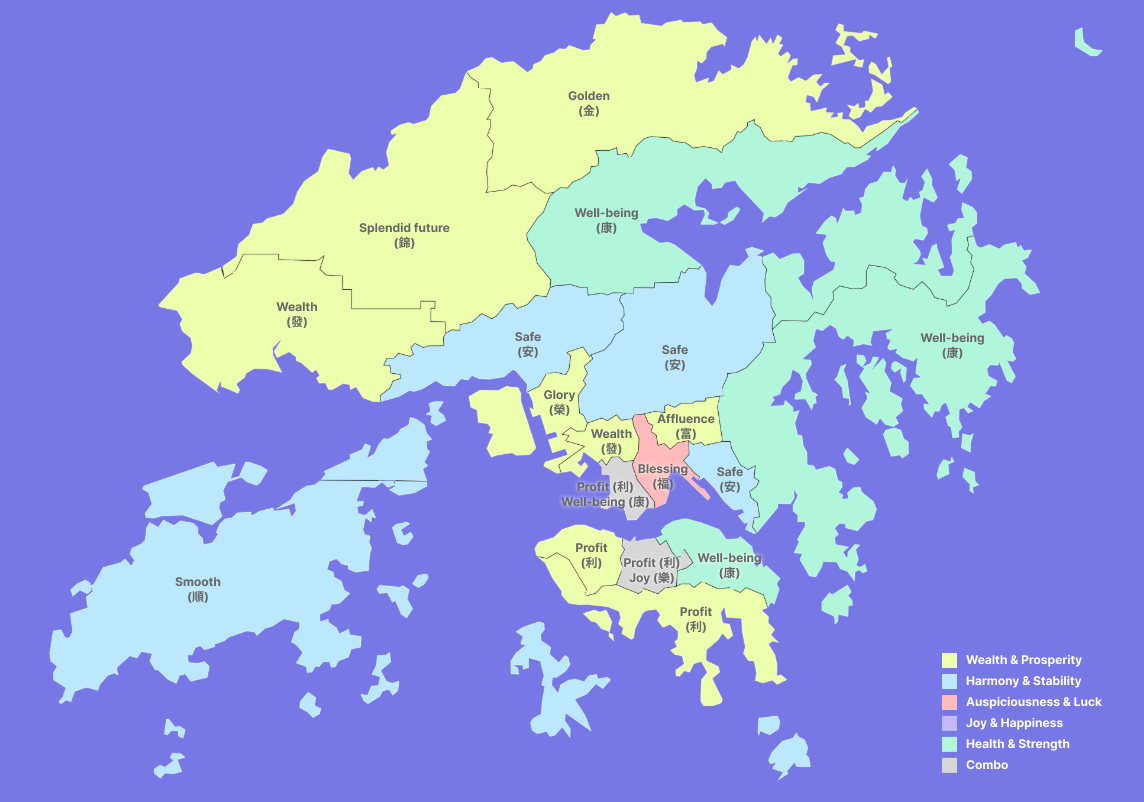

An analysis of more than 4,600 street names reveals the city’s aspirations. Prosperity dominates, with 14% of names drawing on characters associated with wealth and success, a fitting reflection of a place built on trade and commerce. Harmony and stability follow at 7%, reflecting a history punctuated by piracy, plague, and the friction of colonial rule. Luck and auspiciousness account for 3.5%, highlighting cultural traditions that value fortune. Happiness and health both hover around 3%, providing modest but telling indicators of everyday hopes.

Check out the data visualisation below to explore how different districts lean toward different aspirations.

Commercial districts lean heavily towards wealth, profit, and prosperity, reflecting their role as hubs of enterprise. Residential areas more often draw on characters linked to health, strength, and wellbeing, signalling everyday concerns for family life and resilience. These naming traditions form a cultural geography in which aspirations for fortune coexist with desires for stability and vitality.

Wealth and Prosperity

Prosperity is written into Hong Kong’s streets with striking regularity, and its spatial distribution reveals much about the city’s history. Characters linked to wealth and profit cluster in commercial districts, reflecting the mercantile foundations on which the city was built.

Profit by Design

Profit (利, lei6) is among the most common auspicious characters in Hong Kong’s street names. Around 60% of streets containing 利 are found on Hong Kong Island, a concentration shaped by the island’s early colonial development. Many of these names were born of a clever linguistic duality. English originals were transliterated into Chinese not just for sound, but for a specific commercial undertone. Elgin Street (伊利近街), Stanley Street (士丹利街), and Murray Road (美利道) show how phonetic resemblance was subtly reshaped to carry auspicious meaning.

In Kowloon, the logic became especially visible during the 1920s expansion. Fife Street, a nod to a Scottish county with no inherent financial meaning, became Faai Fu Gaai (快富街, ‘Quick Affluence Street’). Bedford Road was rendered as Bit Faat Dou (必發道, ‘Must Prosper Road’), using the character 發 (faat3) to recast a suburban name as an economic prophecy. Elsewhere, the "–ford" suffix was frequently softened into 福 (fuk1), meaning ‘blessing,’ turning a neutral English reference into a permanent lucky charm.

Proof that HK can turn even a Scottish town into a business plan (source: yahoo HK)

Bedford Road stands as a quiet lesson in how HK rewrites meaning (source: wiki)

The Industrial Prospectus

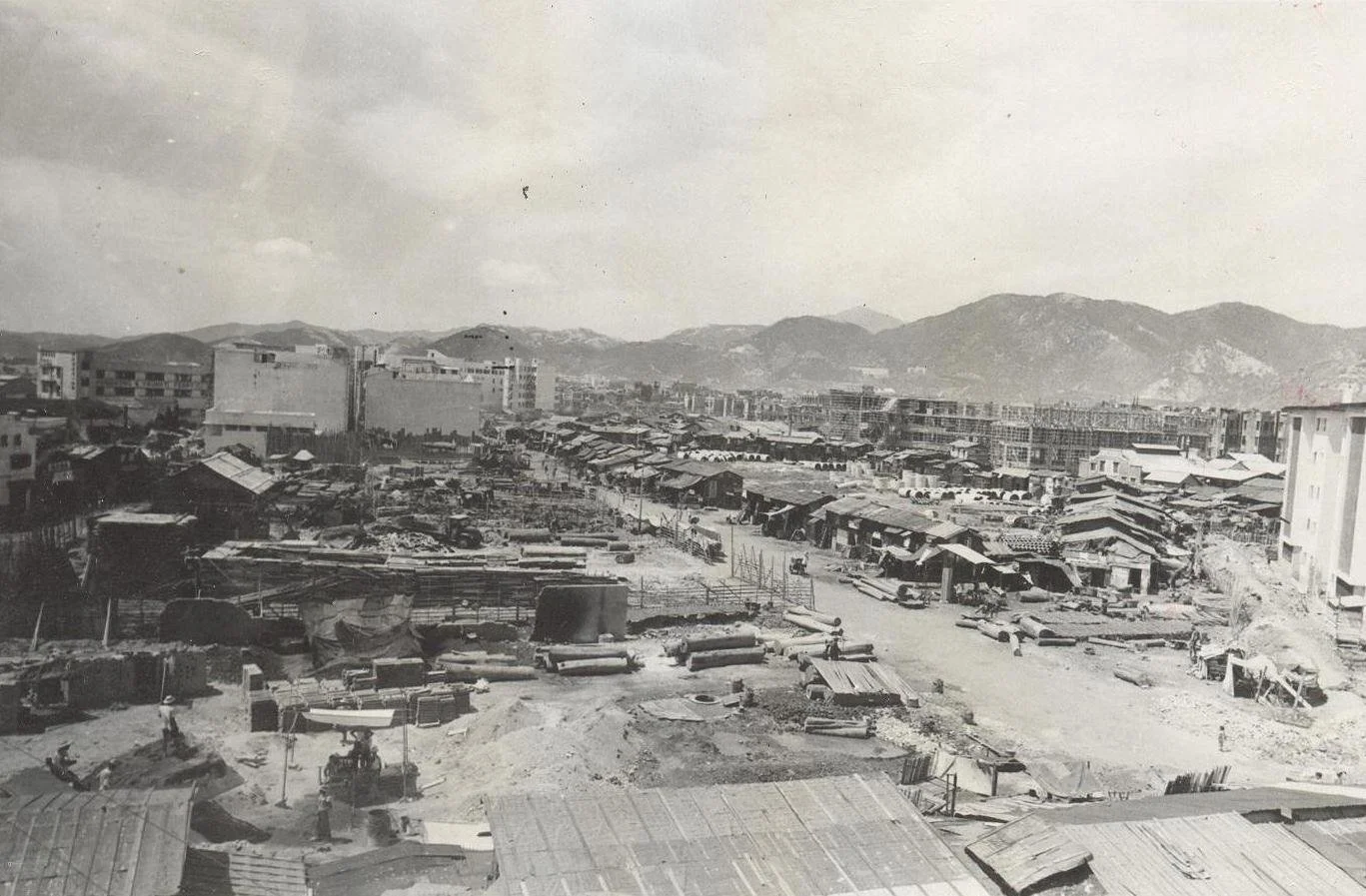

Workshops in Tai Kok Tsui in 1955 (source: HK Public Records Office)

Post-war industrialisation transformed prosperity from a hope into a planning tool. In the 1950s, Kwun Tong, one of the city’s first satellite industrial hubs, adopted a naming convention that functioned almost as corporate branding. Hung To Road (鴻圖道, ‘Grand Plan Road’), Hoi Yuen Road (開源道, ‘Origin of Wealth Road’), and Chong Yip Street (創業街, ‘Start Enterprise Street’) marketed industrial toil as a form of destiny.

In the 1960s, the redeveloped Tai Kok Tsui offered Foo Kwai Street (富貴街, ‘Rich and Esteemed Street’) and Li Tak Street (利得街, ‘Profit Arrive Street’), promising that factory work would translate into social status.

By the 1970s, Tai Po's Industrial Estate had marked the bureaucratisation of luck. Built in 1974, it used the prefix Dai (大, "Great") to create a rhythmic litany of ambition: Dai Li Street (大利街, Great Profit Street), Dai Fu Street (大富街, Great Richness Street), Dai Fat Street (大發街, Great Wealth Street), and Dai Kwai Street (大貴街, Great Esteemed Street). The repetition formed a linguistic grid of promises, projecting economic progress as destiny etched into the estate's streets.

Tuen Mun, too, bears this industrial stamp. The character for wealth/expansion (發, faat3) is uniquely prominent here, appearing in 30% of such street names territory-wide. As Tuen Mun shifted from a rural hinterland to a powerhouse of brickworks, shipyards, and power stations, its streets were named to mirror its new identity as a gateway for settlement and a centre of production.

The Lucky Grid

The eight lucky streets in San Po Kong, taken in 1972 (source: HK Memory)

The most striking example of industrial linguistic engineering lies in San Po Kong. Developed in the 1950s and 1960s, the district was first laid out as a numerical grid: First through Eighth Street. As the industrial boom gathered pace, this utilitarian scheme was systematically replaced with auspicious characters, each number exchanged for a phrase of fortune.

“First” became Tai Yau Street (大有街, Great Abundance), “Second” became Sheung Hei Street (雙喜街, Double Joy), and the sequence continued until “Eighth” was transformed into Pat Tat Street (八達街, Eight Attainments/Prosperity). The grid was recast as a geomantic prospectus, projecting prosperity onto its factories and workshops.

The ingenuity extended further. Tai Yau Street connects directly to Tseuk Luk Street (爵祿街), which carried a double resonance. On the surface, the name suggested noble rank and salary; in practice, it was a phonetic rendering of “landing” (著陸, zoek6 luk6), marking the site of Kai Tak Airport’s runway. Aviation history was folded into the industrial grid, a pun that fused fortune with flight. This layering of auspicious meaning and practical geography makes San Po Kong the most comprehensive and symbolically rich case of industrial naming in Hong Kong.

| Street Name | Literal Meaning | Industrial Projection |

|---|---|---|

| Tai Yau Street (大有街) | Great Abundance Street | Ambition, high returns, comprehensive wealth |

| Sheung Hei Street (雙喜街) | Double Joy Street | Success in both business and personal life |

| Sam Chuk Street (三祝街) | Three Blessings Street | Longevity, prosperity, posterity |

| Sze Mei Street (四美街) | Four Beauties Street | Refinement, overcoming number 4 taboo |

| Ng Fong Street (五芳街) | Five Fragrances Street | Virtue, reputation, moral standing |

| Luk Hop Street (六合街) | Six Harmonies Street | Cooperation, balance, smooth operations |

| Tsat Po Street (七寶街) | Seven Treasures Street | Rarity, ultimate value, lasting wealth |

| Pat Tat Street (八達街) | Eight Attainments Street | Fortune reaching success in all directions |

Inherited Luck

Money, money, money, must be funny (source: house730)

Not all auspiciousness was top-down. Many names were inherited from the landscape itself or deep-rooted local traditions. The "splendid future" (錦, gam2) found in Kam Tin and the "affluence" (富, fu3) of Lok Fu suggest that planners often had to respect the linguistic history already on the ground.

Yuen Long offers perhaps the most vivid case. Over 87% of streets containing Golden (金, gam1) are located here, a concentration rooted in geomantic tradition. Kam Tsin Village (金錢村, Gold Coin Village), an ancestral settlement of the Hau Clan, exemplifies this logic. Geomancers read the hill behind the village as a butterfly poised above a coin, a landscape where joy and transformation danced with perpetual prosperity. Naming practices fused landscape, symbolism, and aspiration into a civic narrative that endures.

Harmony and Stability

If prosperity mapped ambition into the city’s streets, stability offered reassurance. Where wealth dominated commercial districts, harmony and safety threaded through residential lanes, reminding Hong Kong that fortune endured only when anchored in order.

The Duality of Peace

Few names capture the friction between colonial aspiration and lived reality as vividly as Tai Ping Shan (太平山, ‘Great Peace Hill’). In the nineteenth century, the title was claimed by two worlds.

The first was Victoria Peak. Following the 1809 Battle of Chek Lap Kok, the pirate lord Cheung Po Tsai surrendered to government forces. Local fishermen, believing an era of chaos had ended, christened the heights "Peace Hill." The second was the warren of Chinese tenements on the mountain’s lower slopes. By 1894, this overcrowded district became the epicentre of the Bubonic Plague. The outbreak laid bare the grim realities of colonial neglect, turning a name signifying "Great Peace" into a bitter irony.

In the wake of the plague, mass clearances made way for a new municipal philosophy: naming as a form of hygiene. Tai On Terrace (大安臺, ‘Great Safety Terrace’), Fuk On Lane (福安里, ‘Blessing and Safety Lane’), and Wa Ning Lane (華寧里, ‘Chinese Quietude Lane’) were gazetted as civic assurances, linguistic reinforcements of sanitary reform and the promise of order restored.

Victoria Harbour with Victoria Peak in the background circa 1865 (source: wiki)

Whole blocks of Tai Ping Shan were torn down and rebuilt with proper drainage and better ventilation., taken in 1898, four years after the plague struck (source: wiki)

The Politics of Naming

On Po On Road, the politics of reassurance are written in plain sight

Street names often functioned as quiet instruments of state reassurance, adapting to the city’s shifting anxieties. The history of Po On Road (保安道) is a case study in this subtle recalibration. Originally a reference to Bao’an across the border (written as 寶安, ‘Precious Peace’), the characters were later altered to signify ‘Security’ (保安).

While local lore often suggests the change was a response to the 1967 riots, government directories from the early 1960s show the ‘Security’ variant was already in use. Regardless of the exact date, the shift from "peace" to "security" reflects a hardening of the colonial climate. In a quirk of history, Po On Road was also the site of the school attended by John Lee, the future Chief Executive and architect of the city’s National Security Law, a coincidence that reads like a topographic foreshadowing of Hong Kong’s modern preoccupation with control.

Safe Passage

Stability was not merely a matter of civic discipline; it was a prayer for safe passage. The character seon6 (順, ‘smooth’ or ‘favourable’) carries a specific promise of ease in travel. Its presence is most concentrated on Lantau Island, the site of the International Airport and the city’s gateway to the world.

Here, auspicious naming is baked into the infrastructure of movement. Shun Lin Road (順連路, ‘Smooth Connection Road’) promises unbroken links, while Cheong Shun Road (暢順路, ‘Clear and Smooth Road’) evokes the effortless flow required by a global logistics hub. Shun Chit Road (順捷路, ‘Smooth and Quick Road’) emphasises the efficiency of the "speed-link," and Shun Lui Road (順旅路, ‘Smooth Journey Road’) speaks directly to the passenger's experience.

Auspiciousness & Luck

In Hong Kong, auspiciousness is a civic layer inscribed into the streetscape. Characters such as 福 (fuk1, blessing), 運 (wan6, luck), and 吉 (gat1, auspicious) encode cultural memory, revealing how fortune was imagined across scales, from the ancestral village to the global gateway.

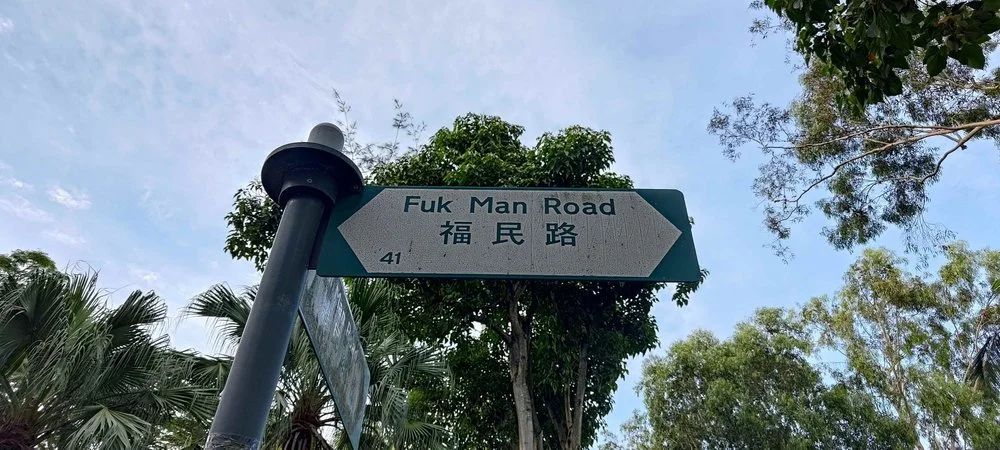

Blessings for the People

Few characters are as enduring as 福 (fuk1), a foundational promise of blessing. However, for anyone who doesn’t read Chinese, its romanisation has also made it an accidental star of internet memes. Fuk Man Road (福民路, “Blessed People’s Road”) invokes collective wellbeing, while Man Fuk Road (文福道) has achieved a kind of unintended online fame for reasons that have nothing to do with its meaning.

In the New Territories, the resonance of 福 deepens into the landscape. Fook Yum Road (福蔭道, “Blessed Shelter Road”) offers the protective shade of auspiciousness, and Fuk Loi Lane (福來里, “Fortune Arrives Lane”) promises blessing at the doorstep. Even Fuk Lo Tsuen (福佬村), a name linked to the Hokkien community, shows how 福 was embedded in local identity as much as in aspirational planning — a character that could signal heritage, hope, and, occasionally, a viral misunderstanding.

Proof that tones matter, even if the internet pretends they don’t (source: HK Hike)

A wholesome name with an unwholesome fanbase (source: HK Hike)

Luck in Motion

In the lexicon of Hong Kong’s streets, the character 運 (wan6) carries a potent duality: it signifies both fortune and transport. This linguistic overlap made it a natural choice for the areas surrounding Kai Tak, which was the site of the city's former airport.

Hung Wan Street (鴻運街, ‘Great Luck Street’) declared fortune arriving in abundance, a fitting sentiment for a district defined by the high stakes of aviation. Olympic Avenue (世運道, ‘World Luck Road’) linked local fortune to international achievement, while Cheong Wan Road (暢運道, ‘Smooth Luck Road’) near Hung Hom Station combined luck with effortless flow.

In Tai Po, this resonance stretches back to the late Qing era. Wan Tau Tong Village (運頭塘村) was established long before the British lease of the New Territories. Local oral tradition later interpreted the name as hung wan dong tau (鴻運當頭, ‘Great luck at the forefront’), suggesting a village positioned at the very precipice of prosperity.

Encounters with Auspiciousness

The character 吉 (gat1, lucky) appears most frequently in Hakka settlements and coastal outposts. Fung Kat Heung Road (逢吉鄉路, ‘Meeting Luck Village Road’) reflects the Hakka tradition of naming places after auspicious encounters or arrivals.

Further north, Kat O (吉澳, ‘Lucky Bay’) embodies a practical, geomantic logic. The island’s deep curves create a natural sanctuary at Kat O Wan, where generations of fishermen sought shelter from typhoons. It became known as "Auspicious Bay" because the geography itself provided safety. In these coastal names, luck was a matter of survival, tied to the rhythms of the wind and the sea.

Kat O - the Auspicious Bay (source: geopark.gov.hk)

Health & Strength

In Hong Kong’s post-war decades, an era defined by overcrowding, poor sanitation, and the trauma of mass resettlement, health became a form of civic reassurance. By the 1960s and 1970s, as the government expanded its housing and welfare programmes, the language of physical wellbeing was embedded directly into the new urban landscape.

The Healthy Village

This logic is most palpable in North Point’s Healthy Village (健康村). When the Hong Kong Housing Society redeveloped a squatter settlement here in the 1960s, it chose to retain the original name. In the climate of post-war recovery, the decision functioned as a manifesto, assuring residents that their new concrete homes offered a promise of vitality. Daily life unfolded beneath a trio of signboards: Healthy Street East (健康東街), Central (健康中街), and West (健康西街).

Healthy Village in the 60s (source: Housing Society)

Auspicious by Mistake

Sometimes, auspiciousness arrives through administrative blunder. In the 1970s, Kwai Chung’s Kin Hong Street (建康街, ‘Building Health’) was accidentally recorded as 健康街 (‘Healthy Street’). Its neighbour, Kin Chuen Street (建全街, ‘Building Wholeness’), underwent a similar shift to 健全街 (‘Robust Street’). These clerical slips endured for 32 years, becoming fixed in local memory and postal records. By the time officials identified the anomaly, the "wrong" names were deemed unassailable.

The error was more than a technicality. The original character Kin (建, ‘to build’) implied a process of effort or aspiration. The accidental replacement, Kin (健, ‘robust’), suggested that vitality had already been achieved. Through a stroke of a bureaucrat’s pen, these streets were transformed from places of striving into sites of fulfilled fortune.

Chik Tsun Wai: accumulating blessings since 1574 (source: Time Out HK)

Accumulating Blessings and Years

In Tai Wai, naming carries the weight of centuries. The walled village of Chik Tsun Wai (積存圍), founded in 1574, was built on the Confucian ethos of "accumulating virtue and preserving benevolence." When Tai Wai was transformed into a New Town in the 1980s, planners adopted this ancestral logic of "accumulation" for the modern grid.

The resulting street names form a litany of gathered blessings, but those dedicated to bodily endurance are the most striking. Chik Sau (積壽, ‘Accumulated Longevity’) and Chik Tai (積泰, ‘Accumulated Peace’) inscribe the hope for a long life into the pavement. In Tai Wai, the street sign acts as a ledger, recording a collective desire for a future as enduring as the neighbourhood's Ming-dynasty past.

Joy & Happiness

By the 1970s, joy had become a deliberate planning motif. In the burgeoning New Towns, the character lok (樂, joy/harmony) was deployed as a thematic affix to soften the edges of utilitarian estates.

Happy Valley’s Irony

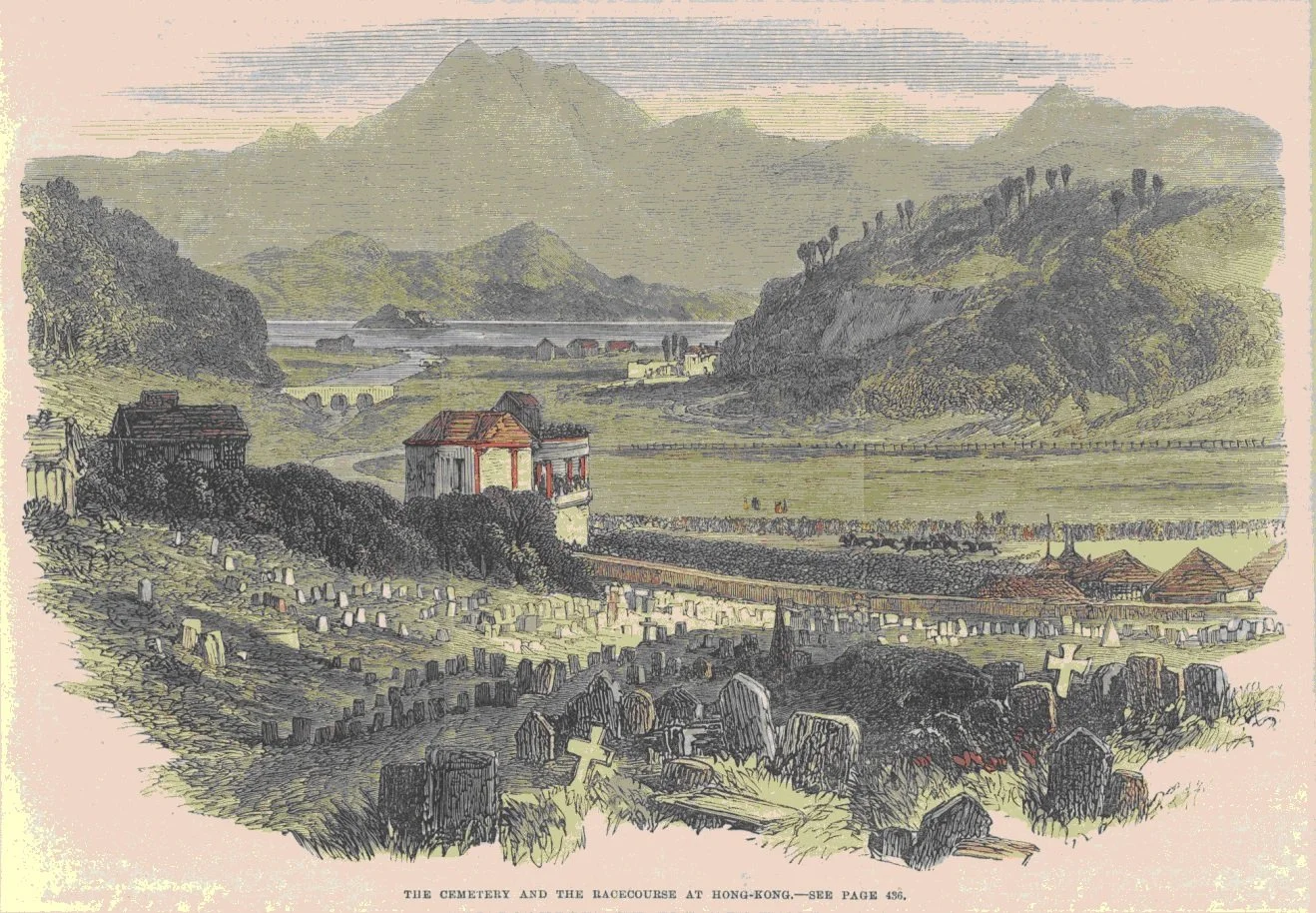

The city’s most famous marker of joy is Happy Valley. Known functionally in Cantonese as Paau Ma Dei (‘Racecourse Ground’), its auspicious name, Faai Wut Guk (快活谷, ‘Happy Valley’), is a direct translation of the English.

The name, however, began as a dark euphemism. Before the marshland was drained in the 1840s, the valley was a malarial swamp. The staggering death toll among early European settlers turned the surrounding hillsides into a cemetery; "Happy Valley" was the Victorian era’s linguistic attempt to overwrite the graveyard with cheer. Even as the racecourse transformed the area into a hub of leisure, tragedy remained. In 1918, a catastrophic fire at the grandstand claimed hundreds of lives, marking one of the deadliest disasters in Hong Kong’s history.

Nearby, Broadwood Road (樂活道, ‘Joyful Living’) completed this transformation. Originally named after a British Major-General, the road’s later Chinese rendering reframed a colonial military reference into a promise of vitality. Today, Happy Valley stands as a linguistic palimpsest, where the memory of loss is buried beneath layers of auspicious optimism.

Happy Valley, before the happiness: where the only crowds were headstones, from the Illustrated London News, May 1866 (source: HK Memory)

Happy Valley on a Wednesday: the city dancing on top of its own history (source: Trip Advisor)

Taming the Tiger

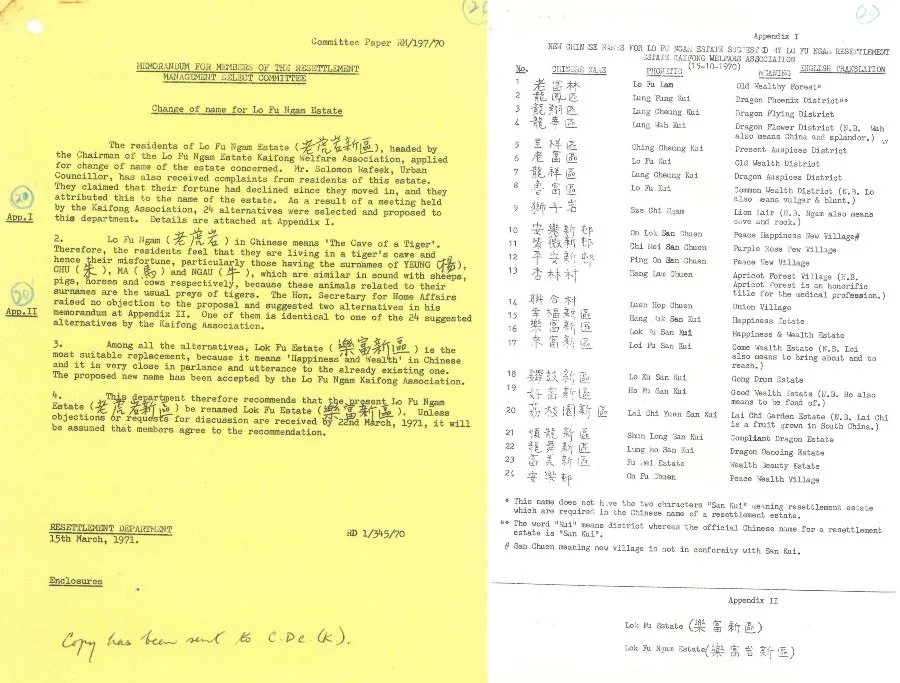

Joy was also summoned defensively, used as a charm to silence local fear. Until the 1970s, a district in the Kowloon Hills bore the unsettling name of Lou Fu Ngaam (老虎岩, ‘Tiger Rock’). In Chinese folklore the tiger is an omen of danger, and families whose surnames echoed prey animals—Yeung (楊, sheep), Chu (朱, pig), Ma (馬, horse) worried that living in the predator’s path invited symbolic disaster.

After local committees and feng shui consultants debated 24 alternatives, the district was renamed Lok Fu (樂富, ‘Happiness and Wealth’). The new name retained a rhythmic echo of the old "Tiger" while effectively shedding its claws. The predator's shadow gave way to a "valley of optimism," and the name Lok Fu became synonymous with the modern housing estates that define the area today.

The official record of Hong Kong’s most delicate tiger‑taming exercise, taken from a governmental document from the 1970s (source: Our China Story)

Conclusion

From ancestral villages to industrial grids, Hong Kong’s map records both its anxieties and ambitions. Street names are small but enduring acts of civic optimism—sometimes heartfelt, sometimes calculated—that shape how residents move through a city in constant flux. Whether silencing a predator or summoning a fortune, the street sign marks the precise point where state planning meets local belief. In a city defined by transience, these auspicious names offer a sense of permanent, promised stability.

Next Up

If the renaming of Lok Fu demonstrated a bureaucrat’s power to declaw a tiger, our next instalment tracks the celestial creatures guarding Hong Kong’s corners. From dragons and phoenixes to qilin and cranes, we trace how ancient myth is enlisted to sell modern real estate, ensuring the city’s luck remains under permanent construction.