Naming the Unnameable

How Superstition Shapes Hong Kong’s Streets

In Hong Kong, superstition isn't just a cultural curiosity, it's a fundamental force shaping the city's very identity. The ancient practice of fung shui (風水 literally meaning wind water), which seeks to balance environments with natural forces, is so influential that nearly 40% of property developers still consult masters to ensure their designs attract good fortune. Mountains are seen as guardians, water as a conduit for prosperity.

The fung shui battle between two giants… allegedly (source: datosfreak.org)

Fung shui's influence on architecture has even given rise to urban legends. The Bank of China’s blade-like tower is rumoured to channel misfortune toward HSBC’s headquarters. After a string of market dips, HSBC allegedly retaliated, installing rooftop structures shaped like cranes, aimed like cannons at its rival. While fung shui may guide billion-dollar blueprints, it has also been known to reroute millions from the bank accounts into the pockets of self-proclaimed masters, proof that in Hong Kong, even superstition comes with an invoice.

This deep-seated mystical mindset doesn't just shape buildings; it also moulds language. The names given to places are seen as tools for attracting good fortune or warding off bad luck. This two-part series explores how fung shui and auspicious thinking influence not only what is built, but what it is named. In this first chapter, we examine Hong Kong’s street names are haunted by homophones, tonal echoes, and linguistic taboos.

But Why?

Lai Chi Wo and its surrounding fung shui wood (source: Go HK)

Why does superstition persist in a hyper-modern city like Hong Kong? Its origins lie in the region's agrarian and maritime past. For early farmers and fishermen, survival depended on appeasing nature’s whims. Villages were laid out according to fung shui principles, with “fung shui woods” (風水林) planted and fishponds dug to guard against calamity. Fisherfolks lit incense and cast offerings into the sea, hoping to placate unseen forces.

These ancient practices weren’t just symbolic, they shaped entire communities. An enduring example is Lai Chi Wo, a 400-year-old Hakka village nestled in the northeast New Territories. According to local lore, a fung shui master once advised villagers to build a wall to trap wealth and deflect misfortune. The village’s fortunes soon reversed, producing scholars and prosperity. To this day, residents fiercely protect the surrounding fung shui woods.

While Lai Chi Wo preserves these traditions in their original form, across the city, such practices have evolved. What began as pragmatic survival strategies have become cultural rituals. Sociologists suggest that these beliefs now offer psychological comfort amid rapid urban change and existential uncertainty. In a city with low formal religious affiliation, superstition remains remarkably resilient, preserved as both heritage and quiet antidote to the chaos of modern life.

Dance with Death

In Hong Kong, death is both taboo and tradition. Beneath the city’s modern veneer lies a deep reverence for ancestors. The Hungry Ghost Festival (盂蘭節) transforms streets into smoky altars, where families burn paper replicas of handbags and sports cars to appease roaming spirits. The practice is so widespread that Gucci once raised concerns over counterfeit offerings.

Equally solemn is Ching Ming Festival (清明節 ‘tomb sweeping day’), held each April. Families clean ancestral graves, offer food and incense, and share symbolic meals with the dead. In a city where space is scarce and silence surrounds death, these rituals speak volumes.

Feeding the invisible guests (source: HKFP)

Sweeping tombs during Ching Ming Festival (source: SCMP)

The Unspoken Spectre of Four

Everyone’s nightmare lift (source: Reddit)

Hong Kong’s unease with death is etched into its architecture. Tetraphobia, the fear of the number four, stems from a linguistic coincidence: in Cantonese, “four” (四, sei3) sounds eerily similar to “death” (死, sei2).

The result is a city-wide aversion that shapes architecture and planning. High-rises often skip the fourth floor entirely, jumping from three to five. In a city that blends Asian superstition with Western influences, the thirteenth floor may also be skipped, sometimes alongside the fourteenth, resulting in a surreal numerical leap from twelve to fifteen in buildings. It is a public design dilemma where planners attempt to exorcise the inevitable from the urban landscape.

Hong Kong’s relationship with death is a quiet negotiation, between reverence and regulation, memory and modernity, presence and absence. It is a city that names the unnameable, not by speaking it aloud, but by designing around it.

High Street: The Fourth Street That Never Was

‘High Street Haunted House’ looking pretty haunted in the 1990s (source: Gwulo)

In Sai Ying Pun (西營盤), meaning “West Camp Site” literally, colonial planners sidestepped the number four, replacing it with a name that carried its own haunted legacy. After British forces established a garrison there in 1841, a grid of steep streets emerged in the 1850s. While the roads followed a sequence—First, Second, Third—the fourth was renamed High Street (高街 gou1 gaai1), a euphemism to avoid the Cantonese sound for death.

At the top of High Street stands the Sai Ying Pun Community Complex, a Grade I historic building with a chilling past. Originally built in 1892 as quarters for European nurses, it later became Hong Kong’s largest mental hospital. During World War II, the Japanese occupation reportedly transformed the site into an execution hall for prisoners of war and dissenters. After its abandonment in 1977, the building fell into disrepair and ravaged by fires, and was nicknamed the ‘High Street Haunted House’.

Today, the building’s granite facade remains, a Victorian shell housing modern government offices. Yet its haunted reputation endures, a reminder that euphemisms may mask discomfort, but they cannot erase history. High Street may have dodged the number four, but it could not escape death.

Po Yan Street: From Burial to Benevolence

In Sheung Wan, death was neither hidden nor sanitised. In the 1850s and 1860s, a surge of refugees from mainland China dramatically increased the population in Taipingshan. Western medicine was widely distrusted, and the terminally ill were often evicted from their homes, left to spend their final days in so-called “dying houses”, among them, the Kwong Fuk I Tsz temple. With no public cemeteries, the dead were buried in shallow graves on nearby hillsides. Monsoon rains frequently exposed the remains, compounding the public health crisis.

Burial grounds for Chinese in 1860s (source: ebay)

Once known as hell on earth - Kwong Fuk I Tsz temple (source: Tung Wah Group)

Fun Mo Street on an old map (source: facebook)

By 1869, conditions had deteriorated to such an extent that Acting Registrar General Alfred Lister launched an investigation. What he found was grim: the dying and the dead lying side by side on squalid ground, without access to medical care. His report ignited outrage in both the Hong Kong and London press.

Under mounting pressure, Governor Richard MacDonnell approved a request from the Chinese community for land to build a hospital. Funded jointly by the colonial government and local donors, Tung Wah Hospital opened in 1870 — the first institution to offer traditional Chinese medicine alongside proper funerary services for the poor and unclaimed.

The transformation was marked not only in infrastructure but in language. Fun Mo Street (墳墓街, “Grave Street”), where the temple once stood, was renamed Po Yan Street (普仁街), meaning “Universal Benevolence.” The new name signalled a shift from abandonment to compassion. In the decades that followed, Tung Wah expanded its mission, establishing mortuaries and charity burial grounds in Sandy Bay and Mount Davis. These efforts redefined how Hong Kong’s Chinese community engaged with death, not as a solitary burden, but as a shared responsibility rooted in dignity and care.

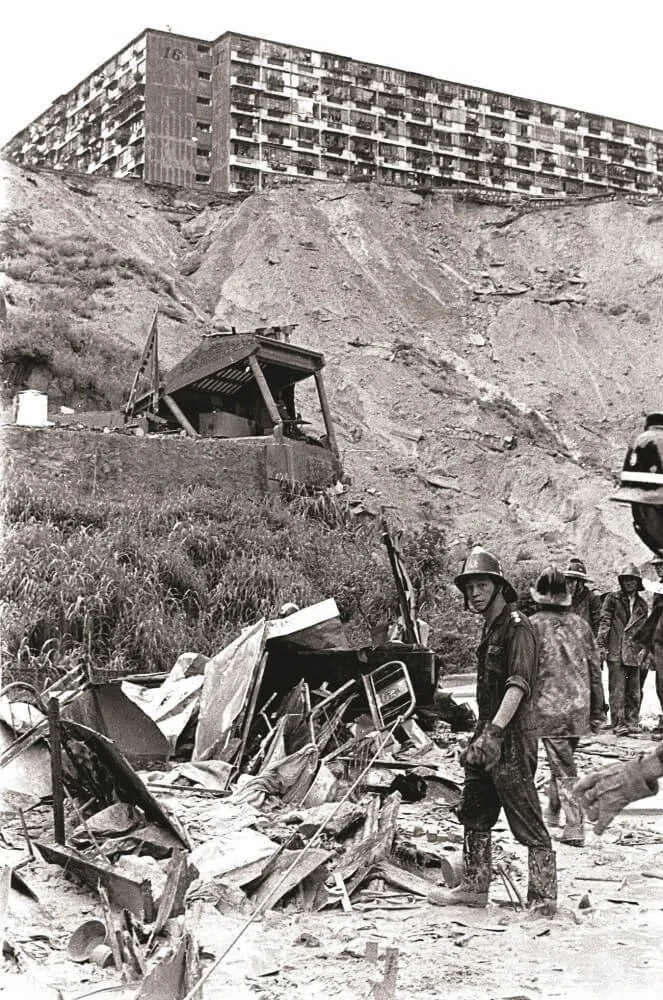

The aftermath of the Sau Mau Ping landslide (source: CEDD)

Sau Mau Ping: A Burial Ground in Name Alone

Elsewhere, death seeped into the soil and the syllables. Sau Mau Ping (秀茂坪), once known as 蘇茅坪 (sou1 maau4 ping4): a grassy plain covered in Chinese skullcap, was romanised under colonial rule as “So Mau Ping.” The transliteration bore an eerie resemblance to 掃墓坪 (sou3 mou6 ping4): “grave-sweeping ground.”

Despite its official renaming in 1962, the name endures as a mnemonic for myth and tragedy. Local lore links the hilltop to wartime executions during the Japanese Occupation and a devastating landslide in 1972 that killed 71 people. These tragedies created a number of ghost stories that continue to haunt the collective imagination.

One tale tells of a teacher who, on a stormy night, sees a mother gently wiping her son's face in the rain. She offers her umbrella, only to recoil in horror as mud pours from their eyes, ears, and mouths. Another recounts a mother and son visiting a nearly empty cinema. When the boy returns from the restroom, the theatre is inexplicably packed. His mother insists no one was there. Only then does he grasp the chilling truth.

Sau Mau Ping may have been renamed, but its spectral associations remain embedded in collective memory.

Tiu Keng Leng: Lives Lived, Lives Lost

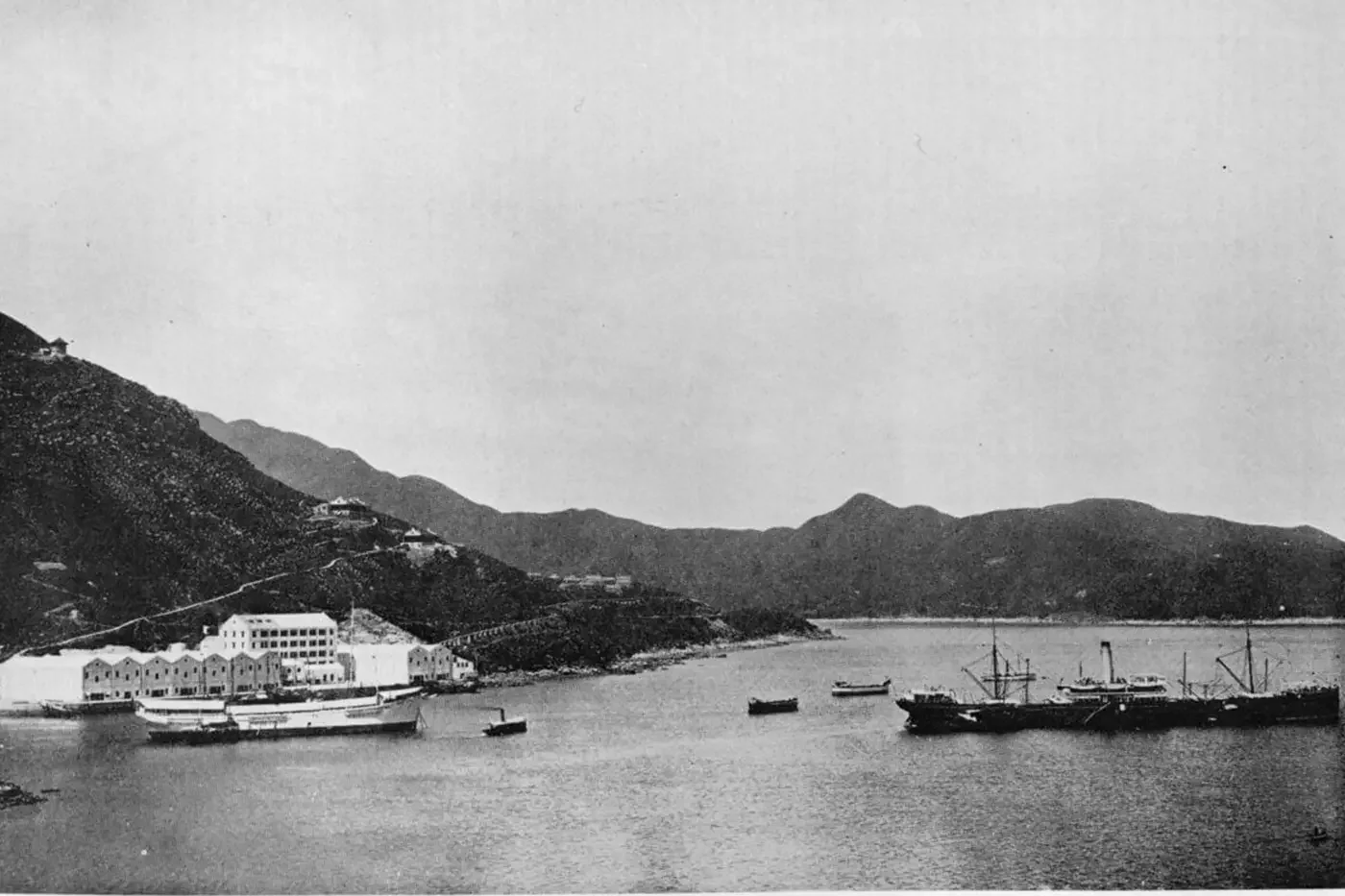

Tiu Keng Leng’s name has carried many lives and deaths. What is now part of Tseung Kwan O once bore several names: “Mirror Ridge” (照鏡嶺 ziu3 geng3 leng5), “Rennie’s Mill,” and at its darkest, “Hangman’s Ridge” (吊頸嶺 diu3 geng2 leng5). The latter two referenced Alfred Rennie, a Canadian merchant who built one of Asia’s largest flour mills before financial collapse led him to take his life in 1908. Though lore claimed he hanged himself in the factory, records suggest he drowned en route.

After the 1946 Chinese Civil War, thousands of Kuomintang refugees fled to Hong Kong, settling in Rennie’s Mill. The enclave operated semi-autonomously, with its own governance, schools, and infrastructure. On ROC holidays such as Double Ten Day and Chiang Kai-shek’s birthday, residents raised the blue-sky-white-sun flag and held patriotic ceremonies, creating a striking contrast to the rest of Hong Kong.

The area was renamed Tiu Keng Leng (調景嶺 tiu4 ging2 leng5), connoting the “adjustment of one’s outlook” (調整景況). Though tolerated by the colonial government, it was reclassified as a resettlement area in 1961 and eventually cleared in 1995 for urban development. Its erasure marked the end of a unique chapter—an exiled Taiwan within British Hong Kong.

Rennie’s Mill in 1907 (source: Zolima)

‘Little Taiwan’ in Tiu Keng Leng before the settlement was demolished in 1996 (Source: jenikirbyhistory)

Map showing Leven Road in 1947 (source: HK Maps)

Lomond Road: Rebranding the Departed

Even foreign names weren’t immune to Cantonese superstition. In the 1930s, Kowloon City’s new Scottish street names included Forfar, Stirling, and Inverness Roads. Yet Leven Road (梨雲道) raised eyebrows. Its Chinese name, 梨雲 (lei4 wan4), phonetically echoed 離魂 (lei4 wan4): “departed spirits.” Its proximity to a hospital heightened the discomfort, and estate agents struggled to sell properties.

Local complaints prompted a swift rebrand. In March 1953, Leven Road became Lomond Road, named after Scotland’s Loch Lomond, with a new Chinese name, 露明道 (lou6 ming4 dou6), meaning “Road of Bright Dew”.

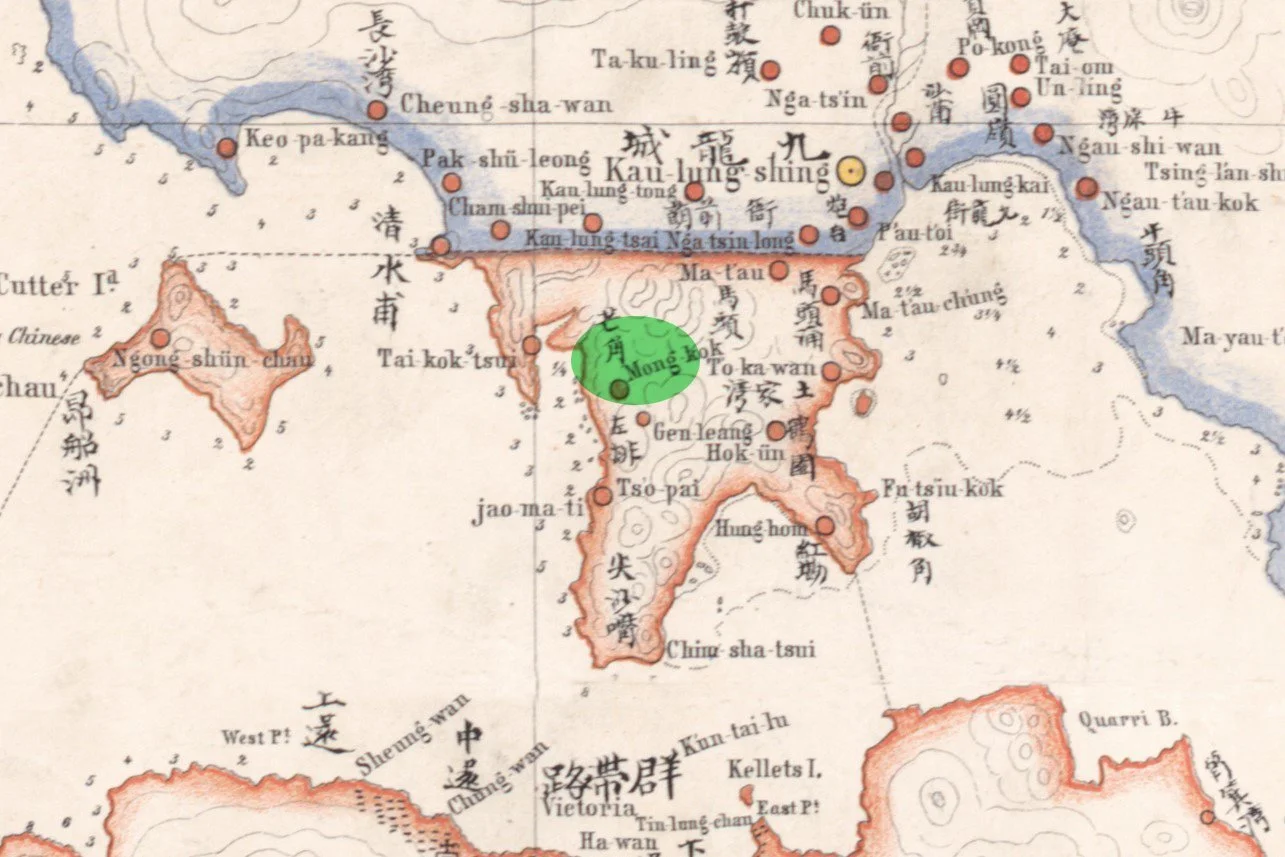

The original Chinese name on 1866 Volonteri's map (source: HK Chronicles)

Mong Kok: A District Rewritten

In Mong Kok, the rebrand was partial—prosperity in one language, death in another. The district’s original Chinese name, 芒角 (“fern corner” mong4 gok3), referenced its lush coastal past. Yet 芒 (mong4) sounded uncomfortably close to 亡 (mong4), meaning “death”, a taboo too stark for Cantonese superstition. Authorities rebranded it as 旺角 (“prosperous corner” wong6 gok3), in the 1930s replacing death’s echo with the promise of fortune.

The English name, however, remained unchanged. "Mong Kok" still echoes its morbid origin, a version of history now erased from local signage. Today, the name professes prosperity in Chinese while quietly retaining its darker undertone in another language.

Haunted by Homophones

In Hong Kong, where fortunes shift with the flick of a trading screen or the turn of a mahjong tile, language is more than communication, it’s strategy. Homophones, words that sound alike but carry vastly different meanings, are treated with caution, especially where money is involved.

When words can tip the scales of fortune, even everyday objects become loaded with meaning. Clocks (鐘, zung1) are rarely given as gifts; the phrase “giving a clock” (送鐘, sung3 zung1) is indistinguishable from attending a funeral. Books (書, syu1) are taboo in gambling circles, their name echoing “loss” (輸, syu1), a linguistic omen frowned upon even in exam halls. In a city where symbolism sways sentiment, and sentiment moves markets, superstition isn’t just cultural, it’s commercial.

Sycamore Street: From Fruitless to Festive

In the neighbourhood of Tai Kok Tsui, streets form a veritable arboretum, where streets were named after a catalogue of trees. Most Chinese translations mirror their English counterparts, though a curious mix-up saw Pine Street (杉樹街) and Fir Street (松樹街) mistakenly swapped in translation. Amid a grove of botanical oddities, Sycamore Street stands apart but not for its foliage, but for its linguistic flourish. Its Chinese name, 詩歌舞街 (si1 go1 mou5 gaai1), translates not to a tree but to “Poetry, Song and Dance Street”, a deliberate departure from botanical convention.

The reason lies in phonetics. “Sycamore” sounds strikingly similar to the fig tree in Chinese: 無花果, meaning “no flowers, no fruit.” Burdened with connotations of barrenness and misfortune, planners abandoned botany for celebrations and transformed a potentially fruitless label into a lyrical emblem of vitality.

Maps showing Shelter Street’s old Chinese name on a map dated around 1960s/1970s. (source: Carousell)

Shelter Street: Where Shelter Once Meant Surrender

Across Victoria Harbour in Causeway Bay, Shelter Street, named after the typhoon shelter nearby once harboured trouble of its own. Its original transliteration, 舒潦濤街 (syu1 lou5 tou4 gaai1) combined comfort with chaos. While 舒 (shu) promised ease, its homophone 輸 (shu) whispered of defeat. This inauspicious undertone was compounded by the characters 潦濤 (lou5 tou4), which sounded similar to 潦倒 (lou5 dou2), a term for hardship and misfortune, creating a name that subtly hinted at ruin.

Seeking to dispel the negative connotations, they renamed it 信德街 (seon3 dak1 gaai1), a near phonetic match meaning “faith and virtue.” Misfortune was out; optimism was in.

Tsuen Wan: The Making of Tsuen Wan

Tsuen Wan marked as Pirate Bay on a 1840 map (source: HK Maps)

Modern-day Tsuen Wan may be known as the New Territories’ first new town, but its name carries echoes of imperial refuge, pirate strongholds, and Hakka resilience. Once called Shallow Bay (淺灣 cin2 waan1), locals found the name ominous, tied to the saying “a dragon stranded in shallow waters, mocked by shrimp.” Seeking better fortune, it became Complete Bay (全灣 cyun4 waan1).

By the Ming and Qing dynasties, Tsuen Wan’s waters had become notorious for piracy. The area earned the moniker 賊灣 (caak6 waan1): Pirate Harbour, with passing ships allegedly paying “three hundred coins” to avoid attack. Even British hydrographic charts from 1810 labelled it the "principal rendezvous of the Pirates."

It was not until the late Qing dynasty that the name Tsuen Wan (荃灣 cyun4 waan1) was formally adopted, a nod to the bamboo fish traps (筌 cyun4) used by the area's fishing communities. This name was proposed by a local scholar and standardised by the colonial government, ending the area's pirate-ridden past and setting it on a new course.

‘Current-suppressing monument’ with Buddhist inscription (source: wikiloc)

Kap Shui Mun: Calming the Currents

Navigational hazards have long shaped the naming of Hong Kong’s waterways. Kap Shui Mun (汲水門), now a vital maritime passage, was once known as Gap Shui Mun (急水門) — “Rapid Waters Gate.” The name reflected the strait’s treacherous conditions: a narrow 180-metre-wide channel with fierce currents and frequent capsizing.

To protect passing vessels, villagers erected stone steles, each around two metres tall, along both shores. These “current-suppressing monuments” (鎮流碑) were believed to pacify the turbulent waters.

Yet the phrase 急水 (“rushing water”) continued to evoke misfortune among seafarers, conjuring fears of floods and fatal crossings. In response, locals adopted a gentler homophone: 汲水 (kap shui), meaning “to draw water.” The renaming reframed the strait’s identity—from peril to sustenance.

Sunny Bay: When Capitalism Took Over

Corporate branding has also reshaped Hong Kong’s map, most notably with the arrival of Disneyland. Yam O (陰澳), meaning “Shaded Bay,” lies along the northern coast of Lantau Island. Once a quiet inlet, it was known for its floating timber yards, where rafts of logs bobbed gently in the sheltered waters, a vital node in Hong Kong’s once-thriving wood trade.

However, the landscape began to shift dramatically in the 1990s. The construction of Chek Lap Kok Airport and the North Lantau Highway triggered extensive land reclamation, dramatically altering the coastline. The bay’s natural contours were disrupted, and its suitability for timber storage diminished. The floating yards faded, and with them, Yam O’s industrial identity.

Enter Disney. As plans for Hong Kong Disneyland took shape, the company sought to distance the site from any associations with gloom or shadow, connotations embedded in the character 陰 (“yam”). The government obliged, rebranding the new MTR station in area 欣澳 (jan1 ou3): “Sunny Bay.” The new name, scrubbed of darkness and infused with cheer, aligned seamlessly with the House of Mouse’s promise of perpetual joy, a linguistic makeover as strategic as it was symbolic.

Timber mill in Yam O in 1972 (source: Industrial History HK)

Choo choo to the land of magic: Sunny Bay MTR station (source: wiki)

Curse by Character

While auspicious symbolism is often deliberately baked into the city’s nomenclature, the inverse is equally true: characters that hint at fear, taboo, or misfortune have quietly vanished from street signs over the years. This subtle sanitisation of language is less about bureaucracy and more about belief, a quiet nod to the city’s deeply embedded superstitions.

Street sign showing Jervois Street’s original Chinese name

Jervois Street: From Fear to Fortune

Take Jervois Street in Sheung Wan. Its original Chinese transliteration, 乍畏街 (zaa3 wai3 gaai1), combines "乍" (sudden) and "畏" (fear), implying unpredictability and dread. Named after Major General William Jervois, who rebuilt the area following a catastrophic fire in 1851, the street eventually flourished into a bustling port for goods from Jiangsu and Zhejiang. In the late 1970s, the street’s Chinese name was renamed to 蘇杭街 (sou1 hong4 gaai1), meaning Suzhou and Hangzhou Street. Only fragments of the original remain, including the signage at No. 112's herbal tea shop.

Subtle Swaps for Good Luck

Similar tweaks occurred on Gleanealy (己連拿利) and D'Aguilar Street (德己立街) in the 1960s and 70s. Both names had featured the character 忌 (gei6), implying avoidance, superstition or taboo. Planners swapped it for 己 (gei2), a neutral alternative that preserved phonetics without invoking bad luck. D’Aguilar Street underwent an additional change. The character 笠 (lap1), which can imply closure or decline, was replaced by 立 (laap6), meaning “to stand”. This subtle change imbued the name with a sense of strength and continuity—an especially desirable trait for a commercial district.

The Ones Left Behind

Yet not all streets received such a linguistic cleansing. Gutzlaff Street (吉士笠街) and Douglas Lane (德忌利士巷) still bear their inauspicious Chinese translations, marked by the same problematic characters. Whether by oversight, apathy, or resistance to change, they serve as a reminder that language itself can carry the weight of fortune.

Luck by Design

The cityscape of Hong Kong looks like a living manuscript, with superstition shaping the edges. A sharp building facade can be seen as a bad sign, while a street name can be seen as a good sign. Here, the physical city is in constant dialogue with the mystical. From skipping the number four to renaming districts for luck, the city’s identity is crafted not just by planners and architects, but by belief itself. These small acts of linguistic cleansing show a place that deals with its deepest fears not by arguing, but by quietly changing things.

Superstition may not appear on the planning application but in Hong Kong, it’s often the most influential consultant in the room. And unlike most consultants, it doesn’t even charge a fee.

Next in the Series

While much attention has been paid to the avoidance of linguistic misfortune in Hong Kong’s urban nomenclature, the deliberate pursuit of auspiciousness is equally revealing. The next chapter turns its focus to the characters and naming conventions that are believed to attract prosperity, harmony, and success, elements deeply embedded in the city’s cultural and commercial fabric.