Beyond Churches & Chapels

Part III: Christianity’s Imprint on Hong Kong’s Streets

Painting of St. John’s Cathedral in 1857 (source)

In Hong Kong, faith is more than just a personal belief; it's a visible part of the city's streets and daily life. From St. Francis Street to Bishop Hill, Christian echoes quietly ripple through the city’s geography, remnants of a once-official creed. At the heart of Central, St. John’s Cathedral still stands on the only piece of freehold land in Hong Kong, granted in perpetuity by Queen Victoria in 1847. While every other plot is leased from the government, this Anglican cathedral remains owned by the Church of England. In 1875, the Public Holidays Ordinance cemented Good Friday, Easter Monday, Whit Monday, and Christmas Day as official holidays.

Christianity’s influence didn’t stop at the cathedral or holidays. It spread through missionary schools, charitable institutions, and social movements that helped mold the city’s identity. Today, Christianity might wear a different face—more commercial sheen than sacred solemnity but its legacy remains, printed not just on shop windows at Christmas and Easter, but on the very map of Hong Kong.

Early Protestant Evangelists

Robert Morrison

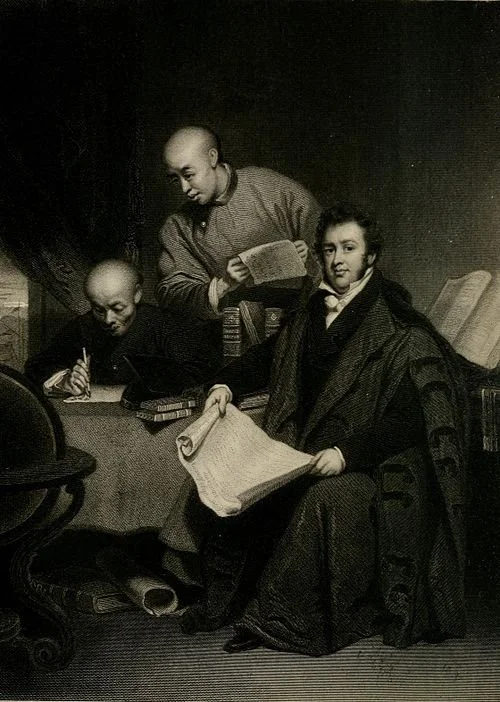

Morrison observes as Li Shigong and Chen Laoyi translate the Bible, 1828 (source: wiki)

In 1807, long before mission schools and churches dotted Hong Kong’s streets, an Anglo-Scottish pastor named Robert Morrison stepped ashore in Macau. Sent by the London Missionary Society, Morrison was the first Protestant missionary to China. He was a linguist, educator, and printing pioneer who set the stage for religious and scholarly exchange that would reach the heart of Hong Kong.

Printing and Linguistic Breakthroughs

To spread Christian teachings, he needed a way to communicate them. By 1815, he had introduced metal movable type for Chinese characters, a leap in local printing capability that shifted how religious texts were produced. In 1823, he completed one of the earliest full translations of the Bible into Chinese, the Shen Tian Sheng Shu (神天聖書). Five years later, he published the first Cantonese-English lexicon, deepening the bridge between English-speaking missionaries and Chinese readers.

Morrison’s eye was always on the next generation. He established the Anglo-Chinese College in Malacca in 1818, a bilingual institute that would relocate to Hong Kong and eventually be known as Ying Wa College. The institution’s legacy endures in name—Ying Wa Street (英華街), marking the spot when the school later moved to Kowloon.

The Hong Kong Type

The printing mission Morrison helped spark found new momentum in Hong Kong. At Ying Wa College, a wave of typographic innovation emerged, led by British missionary Samuel Dyer. Dyer’s collaboration with Chinese artisans culminated in Hong Kong Type (1851), a refined set of movable metal type that mirrored the elegance of traditional woodblock printing. Its adoption by local and international printers signaled not just aesthetic success, but a global reach into the Netheralnds and Russia.

Morrison Hill and Its Transformation

Beyond language and printing, Morrison profoundly shaped Hong Kong’s educational landscape. Following his passing in Guangzhou, the Morrison Education Society was founded in Canton, offering English-language instruction infused with Christian teachings. In 1842, the London Missionary Society secured land near Wan Chai to open a church school in his memory. The hill where it stood became known as Morrison Hill (摩理臣山), a landmark that anchored early English-language education in the city. But it didn’t last. During the Praya East Reclamation in the 1920s, the hill was dismantled. Its rock was carted away via Bowrington Canal, now buried beneath Canal Road. Some of that stone helped form modern streets, including Morrison Street (摩利臣街), named after Morrison’s son.

Excerpt from Chinese Bible - Shen Tian Sheng Shu (source: FB: World Religions Museum)

"Hong Kong Type" lead movable type, 1859 – 1909 (source: HK Heritage Museum)

Karl Gützlaff

Gützlaff in Fujian clothing, 1845 (source: wiki)

While Robert Morrison laid the intellectual foundation for Christianity in China, Karl Gützlaff expanded its reach through commerce and diplomacy. A polyglot and visionary, Gützlaff mastered a staggering range of languages—Chinese, Cantonese, Hakka, Malay, Thai, Japanese, and Cambodian.

Gospel and Gunpowder

Soon after meeting Morrison, Gützlaff immersed himself in Chinese society. He took on a Chinese surname, Guo (郭), naming himself 郭實獵 and promoted the idea that commerce could pave the way for Christianity. As an interpreter for the East India Company, he distributed religious texts alongside cargo manifests; faith and trade, he believed, were not mutually exclusive.

That belief brought him directly into the currents of war. During the First Opium War (1839–1842), Gützlaff emerged as a critical go-between, navigating diplomacy between British officials and Qing authorities. His command of language and etiquette earned him the post of Hong Kong’s first Assistant Chinese Secretary in 1842, later promoted to Chinese Secretary. He also inherited Morrison’s old post, interpreter and secretary to the British Commission on Trade, serving under Morrison’s son.

Scandal and Legacy

But the empire he tried to build on conversion soon faltered. Gützlaff’s most ambitious project, the Chinese Union, aimed to train native evangelists. Instead, it was riddled with fraud. Recruits fabricated conversion reports and siphoned off funds, undermining both his mission and reputation. His vocal support for military-backed missionary work further alienated allies.

Still, his mark on Hong Kong remains. Gützlaff Street (吉士笠街) in Sheung Wan bears the name of a man whose faith was as expansive as his linguistic gifts, and whose legacy sits at the uneasy intersection of idealism, opportunism, and empire.

Chusan Conference: On 4 July 1840, Commodore Bremer met Admiral Zhang Chaofa and senior Mandarins aboard HMS Wellesley in Chusan harbour, on the eve of the island’s capture. Karl Gützlaff, in the middle, served as interpreter. (source: wiki)

The First “Church Villages”

Lighting Things Up in Wanchai

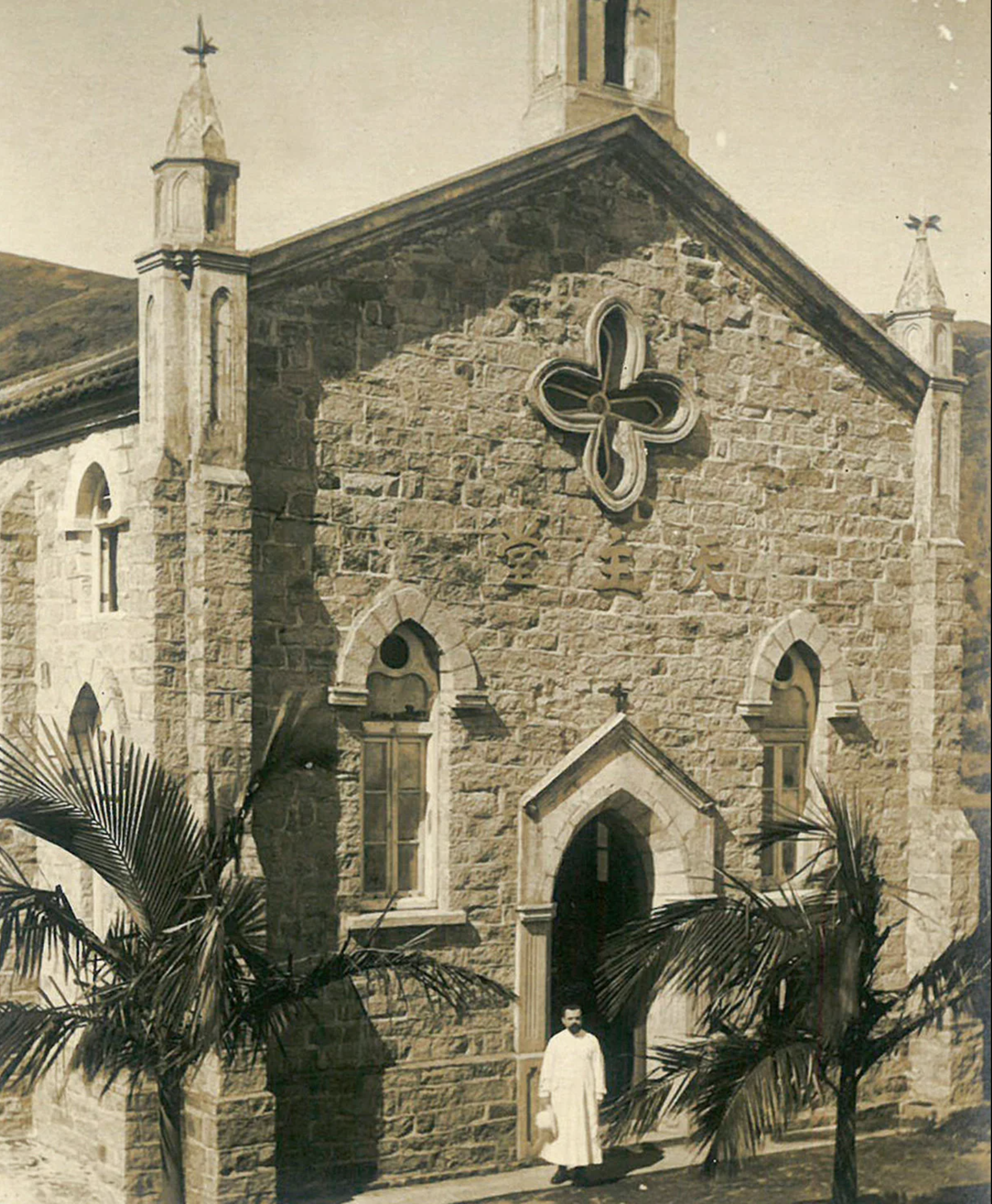

Long before neon signs flickered over Wan Chai, faith carved out one of Hong Kong’s earliest communities. In the early colonial years, Catholic settlers from Macau clustered near Hung Shing Temple, planting spiritual roots where commerce would later take hold. At the heart of this enclave stood St. Francis Xavier Chapel, built by 1845 and flanked by a modest hospital and orphanage. Missionary priests took in abandoned children, and Catholic families built homes around the church, forming a tight-knit “church village.” The sanctuary was demolished in 1922 as Wan Chai urbanised but the memory lingers in the neighbourhood. St. Francis Yard (進教圍) and St. Francis Street (聖佛蘭士街) still trace the outlines of that early congregation.

Bringing Light: Wan Chai Power Station, 1908 (source: wiki)

Just a few blocks away, another vestige of faith remains. Kwong Ming Street (光明街), once Holy Infant Lane (聖嬰孩嬰里), takes its name from a different legacy. In 1848, the Sisters of St. Paul of Chartres founded the Holy Infant Home, a shelter for abandoned children. From that mission grew St. Paul’s Convent School and St. Paul’s Hospital, both landmarks of Catholic care. When electric lighting arrived via the Wan Chai Power Plant in 1925, the street took on a new name: Kwong Ming, or “Illumination,” capturing both physical progress and spiritual light.

Though much of Catholic Wan Chai has been overtaken by tower blocks and traffic, quiet echoes remain. Our Lady of Mount Carmel, now uniquely tucked inside a residential complex, marks the very site of the old St. Francis Chapel. And at nearby Dominion Garden, the black-and-white wave-pattern paving nods subtly to Macau’s Senado Square, a graceful tribute to the city’s Portuguese past.

Our Lady of Mount Carmel keeps watch over Wan Chai from a high-rise building (source: HK Catholic Church)

From Macau to Wan Chai - Dominion Square (source: Pacific Place)

Faith By the Quarry in Shau Kei Wan

As Wan Chai’s church villages took root, Shau Kei Wan was quietly becoming another hub of faith—one shaped by language, labour, and resilience. In the mid-1800s, missionary Karl Gützlaff and the Basel Mission began holding Christian services in Hakka, aiming their message at quarry workers and settlers who made up much of the growing town’s population. That foothold became permanent in 1862 with the area’s first Basel church, remembered today in the name Basel Road (巴色道).

By the early 20th century, Christianity had threaded deeply into local life. The Canossian Sisters established a school and a church on Church Street (教堂街) and Church Lane (教堂里), blending education with worship in the heart of the neighbourhood. Further east, Holy Cross Church rose along Holy Cross Path (聖十字徑), anchoring Catholic life in a community rapidly reshaped by urban expansion.

But faith wasn’t immune to geopolitics. When World War I broke out, German-led missions faced rising suspicion and isolation. Financial and logistical lifelines were cut, and many missionaries were forced to retreat. In response, local Christians stepped up. Chinese-led congregations like the Tsung Tsin Mission of Hong Kong (崇真會) and the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Hong Kong (信義會) took root—proof that Christianity in Hong Kong was no longer an imported ideal but a local inheritance.

Schoolchildren in Shau Ki Wan, 1909.(source: Basel Mission Archives)

Holy Cross Church in the 1930s (source: HK Catholic Archive)

Into The Woods

By the mid-19th century, missionaries in Hong Kong were pushing beyond city limits—into forests, over hills, and deep into Hakka heartland. They brought more than Bibles. With them came chapels, schools, and social institutions that transformed isolated villages, imprinting belief onto the land and the map alike.

Volonteri in full Chinese grab (source: Geographicus Antique Rare Maps)

The Beginnings of Catholic Missions in Sai Kung

Catholic missions in Sai Kung began in the 1860s under the Prefecture Apostolic of Hong Kong. Led by Fr. Simeone Volonteri and Fr. Gaetano Origo, the priests embedded themselves in village life. Faith took root but so did cartography. Volonteri, equal parts clergyman and chronicler, produced some of the most detailed maps of 19th-century Hong Kong, helping the colony understand its own terrain.

Born in Milan in 1831, Volonteri arrived in Hong Kong in 1860 and set out to chart what few dared. Traveling across San On District, now the New Territories, he created Hong Kong’s first bilingual map in 1866. His 1874 update sharpened details of Kowloon and Hong Kong Island, even pinpointing Qing mandarins’ residences. It was dangerous work: unauthorised mapping under Qing rule was viewed as espionage, and villagers, wary of outsiders, fed him false data or blocked his progress. Even so, Volonteri’s maps were remarkably accurate, offering a rare window into an unmapped frontier.

Known locally as Padre Ho, Volonteri found common ground with Hakka rice farmers, who embraced Catholicism more readily than the region’s wealthier Cantonese. He did more than preach, he helped villages resist unjust taxes, organised self-defense against pirate raids, and built alliances that made the Church part of everyday survival. However, his advocacy came at a cost. Rising tensions led to clashes that saw him reassigned to Henan Province in 1870.

Hong Kong’s first bilingual map in 1866 (source: Lord Wilson’s Heritage Trust)

Now largely uninhabited, Yim Tin Tsai (鹽田梓) once flourished under Catholic guidance. There, St. Joseph’s Chapel became both sanctuary and shield against piracy. Though the island declined economically in the 1960s, its Catholic traditions persist. Each May, former residents return to celebrate the parish feast, keeping Hakka prayers alive in an otherwise quiet harbour.

By 1922, Sai Kung counted 1,500 Catholics, ten schools, and twelve catechists. World War II disrupted everything; churches were razed, communities scattered. Still, the Church rebuilt. In 1964, Caritas-Hong Kong resettled Catholic boat dwellers on land, founding villages like St. Peter’s Village (伯多祿村), Tai Ping Village (太平村), and Ming Shun Village (明順村). These faith-rooted settlements embodied the same resilience that had guided missionaries into the wild a century earlier.

St. Joseph’s Chapel (source: HK Tourism Board)

St. Peter’s Village in Sai Kung (source: The Way Catholic)

How Missionary Divided Cheung Chau

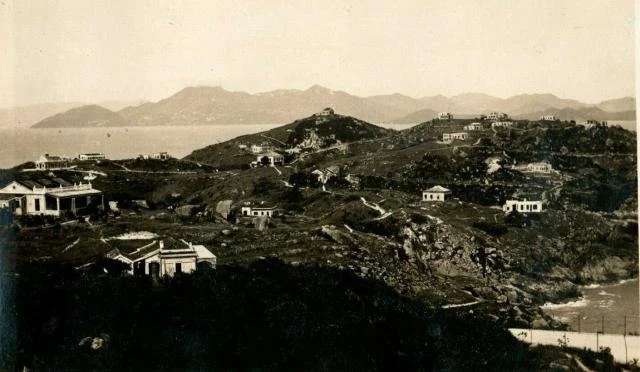

1930s European bungalows on Cheung Chau (source: Gwulo)

By the mid-19th century, Cheung Chau had become a spiritual crossroads. Protestant missionaries arrived in 1843, followed by Catholic orders in the 1860s, bringing with them schools, clinics, and churches that would reshape the island’s landscape. Cheung Chau Church Road (長洲教堂路), Don Bosco Road (思高路), and St. Paul Road (聖保祿徑) remain physical testaments to that legacy.

While missionaries brought education and healthcare, their growing influence reshaped social structures in ways that weren’t always harmonious. Many foreign clergy built homes on the island—not as parish hubs, but as seaside retreats, while continuing to focus on evangelism across mainland China and Southeast Asia. Over time, tensions simmered. In 1919, the colonial government passed the Cheung Chau (Residence) Ordinance, restricting access to the southern coast and effectively drawing a line between foreign residents and local Chinese communities.

That divide, literal and symbolic, lasted for nearly three decades. It wasn’t until the ordinance was repealed in 1946 that the island's communities—once split by faith, race, and regulation—began to converge again.

Sent from Hong Kong’s Acting Governor Claud to Viscount Milner: a copy of the plan highlighting the island area under reservation (source: National Archive: CO 129/455 - RC6269598, cost me £30 and a small piece of my soul to get this map from the archive. No “like, share, subscribe” here but your continued scrolling is very much appreciated.)

To Fung Shan’s Spiritual Fusion

In an age when missionary work often meant cultural dominance, Tao Fong Shan (道風山) offered something different—a quiet, radical departure where Christian theology merged with Buddhist and Taoist sensibilities. Founded in 1930 by Norwegian missionary Karl Ludvig Reichelt, the hilltop retreat in Sha Tin sought not converts, but dialogue.

Reichelt had pioneered similar centres in mainland China before political upheaval drove him south to Hong Kong in 1929. There, he envisioned a sanctuary that could speak the language of Chinese spirituality—literally and architecturally. With Danish architect Johannes Prip-Moller, he designed a complex that echoed Buddhist temples: curved eaves, incense-lined courtyards, and pagoda silhouettes. At its heart stands an octagonal chapel modeled after Beijing’s Temple of Heaven, its carved lotuses and Christian crosses folded into one.

Tao Fong Shan endured air raids, fires, and ideological shifts. Even after a devastating blaze in 1999, the site was painstakingly restored. Today it remains what Reichelt intended: not a fortress of faith, but a meeting place of traditions, a space where incense meets liturgy, and theology finds room to listen.

Where incense meets liturgy—Tao Fong Shan (source: Areopagos)

Another Brick In The Wall

Christian missionaries didn’t just build churches in Hong Kong—they built classrooms. Across the 19th and 20th centuries, they helped shape a city where faith and education became deeply intertwined. As civil wars in China pushed churches to seek refuge, many turned to Hong Kong, transforming overlooked terrain, particularly in Kowloon, into educational strongholds. Today, the legacies of these schools are written into the very map: St. Joseph’s Path (聖若瑟徑), La Salle Road (喇沙利道), Pui Ching Road (培正道), and True Light Lane (真光里) each carry stories of learning grounded in belief.

St. Joseph’s and La Salle: Faith in Flight

Catholic education in Hong Kong gained momentum after the 1874 typhoon ravaged Macau, prompting a wave of Portuguese families to relocate. Six La Salle Brothers followed, arriving on 8 November 1875 to take over the struggling St. Saviour’s College on Staunton Street—renaming it St. Joseph’s College. As migration patterns shifted again in the 1910s, with Kowloon growing rapidly after the Second Convention of Peking, the Brothers expanded across the harbour. By 1932, La Salle College opened its doors in Kowloon Tong, a symbol of education migrating with the city’s pulse.

Pui Ching Road: A School by and for Chinese Christians

Unlike many missionary schools founded by foreign religious orders, Pui Ching Middle School marked a shift toward self-sufficiency in Christian education. Established in 1889 by Chinese believers, it became the first Christian school independent of foreign missions. As political unrest in China escalated, the school expanded to Hong Kong in 1933. Its home on Pui Ching Road reflects not just its physical location, but a philosophical shift—the indigenisation of Christian learning, built by locals and rooted in community.

True Light Lane: Women’s Literacy Takes Root

While most early schools targeted boys, American Presbyterian missionary Harriet Noyes believed women’s education could be transformational. In 1872, she opened the True Light Seminary in Guangzhou with just six girls. Its message traveled. By 1935, a Hong Kong branch—True Light Primary—was teaching girls in Kowloon. The name lives on in True Light Lane, a quiet byway that honours one woman’s defiance of convention and her enduring influence on women’s literacy.

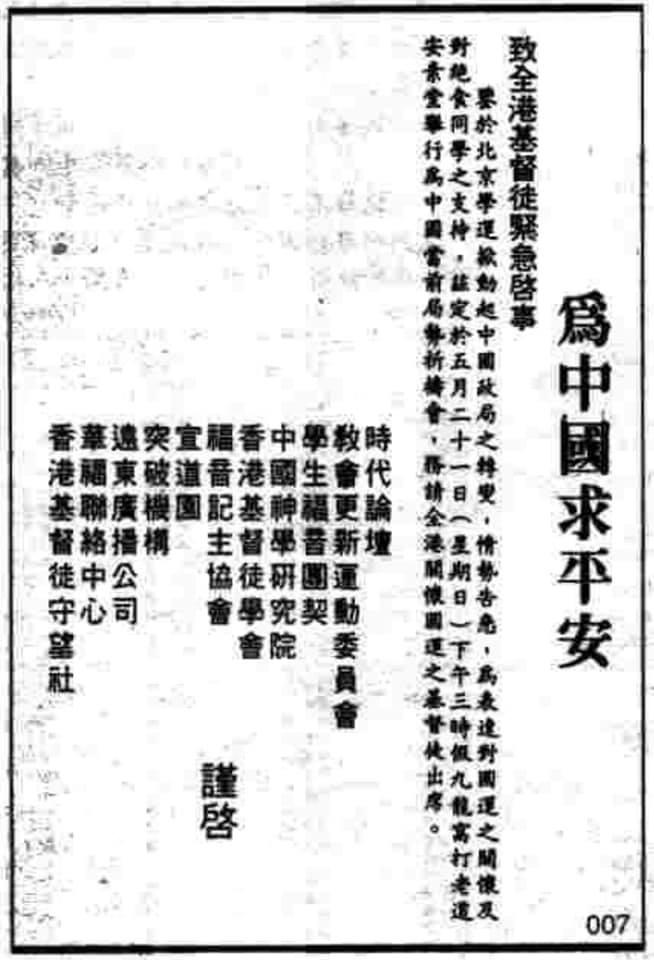

Newspaper notice about the May 21, 1989 prayer congregation (Source: X)

30,000 Voices

Tucked between Yau Ma Tei’s concrete corridors, Chun Yi Lane (真義里) tells a quiet story of faith with deep roots. Its name fuses True Light (真光) and Shun Yi Wui (信義會), the Chinese name for the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Hong Kong, marking a legacy that began with the founding of Lutheran Truth Church in 1954 and True Light Girls’ School in 1973.

That foundation took on public significance on May 21, 1989. As martial law descended on Beijing, nearly 30,000 Christians gathered at Ward Memorial Methodist Church in an act of solidarity and prayer. The crowd overflowed from the sanctuary into Chun Yi Lane, transforming the narrow stretch into an impromptu congregation where hymns echoed between tenements and prayers rose toward uncertain skies.

Fluid Identities

Mission Road (教會道) was always something of a ghost—its name steeped in ecclesiastical resonance, yet tied to no visible church. When it appeared on maps in 1933, no religious institution stood nearby. By 1959, as Kowloon City modernised, the name vanished, replaced by Tin Kwong Road (天光道). Still, that fragment of faith never quite disappeared—its origins murky, its presence lingering as a footnote in the city’s spiritual topography.

Bishop Hill (主教山) tells a similarly layered story. Known today for the ruins of a 20th-century reservoir, it sits between neighborhoods and identities. Some call it Shek Kip Mei Hill (石硤尾山), linking it to the adjacent district. Others prefer Wo Chai Hill (窩仔山, “Little Nest Hill”), a nod to its quiet isolation. Despite its name, there was never a bishop here. The hill’s title likely traces back to the Basel Mission which, in the early colonial period, rented land from the government and built the Basel House atop the hill. Two missionaries lived there, planting the earliest seeds of a Christian presence on the ridge.

Mission Road shown on a map in 1947 (source: Gwulo)

Basel House was the Kowloon Headquarter of Basel Mission built in 1901. Photo taken in 1940s. (source: richardwonghk2@flikr)

Street names in Hong Kong serve more than just as road signs; they also serve as reminders of the city's religious history. They recall a time when Christianity influenced not only cathedrals and public holidays, but also the city's physical layout. From abandoned chapels to hills that once housed missionaries, traces of a spiritual blueprint can still be found on the map. Many of these origins have faded from public memory over time, but some names have endured. As you wait in line for sourdough and cold brew in the Star Street Precinct, it’s worth remembering that nearby St. Francis Street carries the name of a chapel that stood there long before the lattes.