Fish and Stones

Hong Kong’s Resourceful Beginnings

Place names act as historical signposts, offering a fascinating journey through a city's socioeconomic evolution. Hong Kong, once brushed off as "a barren rock," has blossomed from a humble fishing village into a global financial hub. From Quarry Bay to Bank Street, these names illustrate the diverse industries that have fuelled the city's growth—and occasionally, the optimistic aspirations (yes, looking at you, Cyberport). In this three-part series, we'll explore Hong Kong's economic history through the lens of its place names.

1841 Census, (source: The Hong Kong Gazette)

How It Started

To understand how it all began, a glance back to the 1841 census unveils a vastly different economic landscape. While the present-day economy is dominated by the service industry, historical urban areas like Aberdeen and Shek Tong Tsui once thrived with distinctive economic activities.

For instance, Aberdeen, which is referred to as Heongkong in many historical records, is a place that harks back to its roots as a fishing village, an identity that it carries forth into the modern day. This is a stark contrast to Shek Tong Tsui, which, now heavily urbanised, was once characterised by its stone quarries, a testament to a different era of economic activities.

Reflecting on this contrast inevitably prompts one to ponder a significant question: What enduring traces of Hong Kong's early industries can still be found in its place names? How have these places, which once had identities so tied to their industries, evolved and changed over time? And more importantly, how have these changes shaped the city we know today?

Thanks For All the Fish

Surrounded by the South China Sea, Hong Kong has a rich history of fishing dating back to the Song dynasty (960–1279 AD). Historically, the Tanka and Hoklo communities dominated the city's fishing landscape. By 1845, the sampan-dwelling Tanka community constituted a significant 40% of the local population. Simultaneously, the Hoklo community left an indelible mark through salt-making, dried seafood practices, and the Cheung Chau Bun Festival.

Tanka community (source: Port Towns & Urban Cultures)

Get some buns :) (source: Cheapo Guides)

Hong Kong's fishing industry peaked in 1961, employing 53,261 workers and yielding 80,000 tonnes of fish. Today, the industry remains significant, generating 77,000 tonnes valued at HK$2.2 billion. However, the number of local fishermen has plummeted to just 10,320 as of 2022. While some fishing villages have urbanised over time, traces of their once-vibrant history persist. In Aberdeen, the Shek Pai Wan Estate development in the late 1960s honoured the community's fishing heritage by naming streets after the character ‘Yu’ 漁 (fishing). Similarly, as Shau Kei Wan and Tuen Mun evolved into residential areas, new streets starting with the character 'Hoi' 海 (sea) emerged, symbolically linking them to their maritime past.

Tsing Yi, the one that’s not a station (source: Fish of Australia)

Meanwhile, many place names reflect the local production. Take Tsing Yi 青衣 (“Tuskfish”), for instance, other than being just a stop on the Airport Express, this area was once an island abundant with blackspot tusk fish in its surrounding waters, inspiring its fitting namesake in Chinese. Places like Po Yue Wan 鯆魚灣 (“Ray Bay”) and Pak Tso Wan 白鰽灣 (“Sea Bass Bay”) in Cheung Chau, and Lung Ha Wan 龍蝦灣 (“Lobster Bay”) and Yau Yue Wan 魷魚灣 (“Squid Bay”) in Sai Kung echo this theme.

Besides marine terms, some names like Mong Yue Kok 望魚角 ("Watch Fish Corner"), reflect the area's history of fishing. On the other hand, Cha Yue Pai 炸魚排 ("Bomb Fish Raft") refers to the once common yet now illegal practice of fish bombing in Hong Kong. These names weave a compelling story of Hong Kong's maritime past and its changing relationship with the ocean.

The World Is Your Oyster

For over 200 years, oyster farming has been a crucial part of Hong Kong's cultural heritage. Located along the coast of Deep Bay near Lau Fau Shan, this practice flourishes due to the unique mix of saltwater and freshwater in the local seawater, perfect for oyster cultivation. This area has earned the moniker "Oyster Village" for its rich tradition. Despite few direct references to the oyster trade, Sai Kung reflects this heritage with landmarks like Ho Chung 蠔涌 (Oyster Creek) and Ta Ho Tun 打蠔墩 (Oyster Pier).

Since the 1970s, pollution from agricultural development and new towns has impacted the oyster farming industry. Despite these challenges, recent efforts aim to revitalise this practice. The University of Hong Kong has collaborated with the local oyster industry to establish the region's first oyster hatchery, to enhance the sustainability of the oyster industry and restore ecological resources in South China and Hong Kong.

Abandoned oyster farm in Hong Kong (source: Earth.org)

Hemp, Net, Rope

Yau Ma Tei, now a busy urban area, was once a coastal village before reclamation. The name "Yau Ma Tei" is a phonetic transliteration of 油麻地, meaning 'a field of oil and hemp'. In the days before nylon, fishing nets were intricately made from hemp twine, treated with tung oil and other plant saps for resilience. Following each fishing expedition, nets were typically returned to boats for drying or mending—a process involving controlled fires to eradicate soft-shelled organisms, and the use of putty to fill any gaps. The need for these materials stimulated the development of a market along the shore, leading to the naming of the area as "Yau Ma Tei."

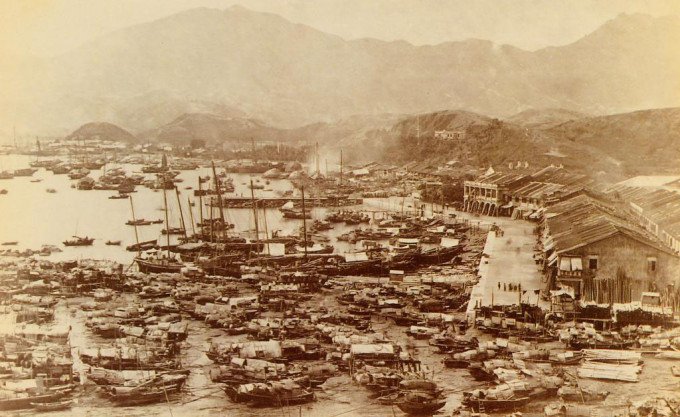

Shore of Yau Ma Tei in 1880 (source: wiki)

Away from the hustle and bustle, Sok Kwu Wan 索罟灣 on Lamma Island owes its name to the fishing gear that was integral to local trade. The term ‘Sok’索 refers to the rope used to secure boats for net-pulling, while ‘罟’ is a reference to a net. Numerous small bays and straits along China's southeast coast carry names that pay tribute to these vital fishing tools.

Hang Them Out To Dry

For countless generations, salted fish has been an essential staple food in coastal Guangdong, sustaining generations of fishermen and fish processors. Dried seafood markets in Hong Kong are located in the oldest, most traditional parts of the city, as well as in fishing villages along the coastline. These shops have been selling an array of dried fish and seafood for over a century. This tradition not only influences culinary habits but also leaves its mark on the urban landscape, like Ham Yu Street 鹹魚街 (Salted Fish Street) in Sai Ying Pun.

Drying fish in Shau Kei Wan in1902 (source: Library of Congress)

Dried seafood shop in Sai Ying Pun (source: TimeOut HK)

Interestingly, Ham Yu Street is one of the few instances in Hong Kong's history where an entire street was relocated. In the 19th century, it sat between Queen's Road West and Des Voeux Road West, with three narrow alleyways housing modest seafood shops. However, the 1894 plague outbreak prompted the demolition of most shops, leading to the street's reconstruction in its current location between Des Voeux Road West and Connaught Road West. The original Ham Yu Street plot was divided into two shorter streets, auctioned off, and developed into buildings adhering to improved hygiene standards.

The old and new Ham Yu Street(s)

On the site of the original Ham Yu Street, two new streets were built – Mui Fong Street 梅芳街 and Kwai Heung Street 桂香街. While it may appear that the tradition of salted fish has faded, its essence endures in the naming of these streets. Known for its distinctive "mui heung" 霉香 (mouldy fragrant) flavour, salted fish inspired the naming of these new streets. However, to avoid the potentially less appetising connotation of "mouldy," authorities opted for a homophone "Mui" 梅 (plum), forging a linguistic connection that preserves the historical essence while adopting a more palatable term.

Getting Salty

The production of salted fish is deeply linked to the ancient practice of salt-working, Hong Kong's oldest industry, which dates back over two thousand years to the third century BC during the Nanyueh dynasty. Outlasting other historical industries like incense-wood production and pearl fishing by over a thousand years, the salt industry was instrumental in early Hong Kong and ancient China relations. The Chinese imperial government, driven by the profitable tax revenues, attempted to monopolise salt production. This led to illegal activities and smuggling, particularly in areas like Tai O. Tensions escalated, peaking during the Song Dynasty in 1197 with armed conflicts between officials and civilians that tragically ended in a massacre of over 300 salt civilians.

Following World War II, the salt industry in Hong Kong witnessed a decline, leading to the conversion of former saltpans in Tai O into the Yim Tin 鹽田 (salt field) Mangrove Forest, where various species of mangroves now thrive. In Sha Tau Kok, another historically significant salt area, place names such as Yim Liu Ha 鹽寮下 (Below the Salt Depot) and 鹽灶下 (Below the Salt Stove) date back to the Ming Dynasty when salt workers were registered based on units of stoves used for salt production. Sai Kung's Yim Tin Tsai 鹽田仔 (small salt pan), stands as a testament to the island's salt industry for over 200 years. The Hakka community who settled there in the 1670s built salt pans and water gates to control the tides, producing valuable salt in high demand. Although Yim Tin Tsai ceased salt production over seventy years ago, the salt fields have remained largely unchanged over the past half-century.

Salt worker in Tai O (source: Industrial History HK)

Yim Tin Tsai in Sai Kung (source: HK Geo Park)

Other references to salt include Yim Tin Kok 鹽田角 (“Salt Pan Corner”) in Tsing Yi and 鹽田仔 (“Small Salt Pan”) in Tai Po. Notably one of the oldest place names in Hong Kong, Kwan Fu Cheung 官富場 (“Field for prospering government”), has a direct linkage to the salt industry, tracing back to the Northern Song Dynasty. Located along the Kowloon Bay coastline, this area once served as an official salt field governed by the imperial court, playing a crucial role in salt production and transportation at the time. Eventually, salt production ceased, and the name evolved into the Kwun Tong 觀塘 we now know.

What Are Men to Rocks and Mountains?

Located within an ancient volcanic belt, Hong Kong has a long history of producing high-quality granite for construction. The origins of quarrying in Hong Kong date back to 1810, when stonemasons were hired to cut stones for a fort in Kowloon. By 1841, masons made up about 22% of Hong Kong's recorded population. The manual task of breaking large stones into small gravel, known as "hitting small stones" 揼石仔, was vital at a time when stone crushers weren't available. This gravel was used in cement production for building houses and required labour-intensive work from entire families.

In 1844, Governor Davis observed villagers quarrying stones along the coastline of Hong Kong Island upon taking office. These quarries were paying taxes to the Chinese government, not the colonial administration. As a result, miners and villagers were required to redirect their tax payments to the colonial government only. Interestingly, quarrying became one of the few local economic activities inaccessible to foreign participation, leading to many entrepreneurial and job opportunities.

Stonecutters breaking stones in1853 (source: HKU)

Stone quarries in 1902 (source: Library of Congress)

During the early Qing Dynasty, the barren hillside near Shek Tong Tsui 石塘咀 attracted Hakka stonemasons, leading to the gradual formation of a significant stone quarry. The portion facing the sea, with its sharp and narrow shape resembling a bird's mouth, earned the name "Shek Tong Tsui" (Stone Pond Point). In Aberdeen, Shek Pai Wan 石排灣 echoes the area's history of quarrying and stone export. Before sellers dispatched them, stones were neatly arranged along Aberdeen's shores, forming rows aptly named "Shek Pai" (Stone Rows), which lent the bay its name.

Old photo of Quarry Bay (source: Randomwire)

Places like Quarry Bay and Stonecutter Island reflect the socio-economic transformation in Hong Kong, with distinct meanings in both Chinese and English tied to their historical activities. Quarry Bay's English name reflects its 19th-century granite quarries, while its Chinese name, 鰂魚涌 (Crucian Carp Stream), nods to its aquatic life. Similarly, Stonecutter Island derives its name from Hakka stonemasons who came to extract stones for Hong Kong Island's construction. Its Chinese name, 昂(仰)船洲 (Upturning Boat Island), recalls fishermen upturning their boats for maintenance, showcasing its maritime history. The dual names of Quarry Bay and Stonecutter Island showcase the convergence of industry, marine activities, and historical transitions in Hong Kong.

The name of Diamond Hill adds another fascinating link to this history. Despite its name, Diamond Hill has never been home to diamonds. The Cantonese name, 鑽石山, is a dual reference to both 'Diamond Hill' and 'Drill Rock Hill,' pointing to the historical stone quarrying operations in the area prior to urban development. Another interpretation suggests that the rocks in the region possessed quartz-like qualities, akin to diamonds.

Quarry structures in Diamond Hill (source: Gwulo)

Though only one quarry remains active, Hong Kong's quarries have left a significant legacy in local landmarks. These include Murray House, the Tea Ware Museum, Béthanie, and the former Tsim Sha Tsui Marine Police Headquarters. Additionally, Hong Kong's granite has been used in overseas projects like the Sacred Heart Cathedral in Guangzhou and the now-demolished Parrott Building in San Francisco, showcasing the global reach of Hong Kong's granite.

Scared Heart Cathedral, aka Stone Chamber in Guangzhou (source: wiki)

Parrott Builing in San Francisco, built in 1851 and demolished in 1926 (source: nesssoftware.com)

My Precious

Ma On Shan Iron Mine (source: wiki)

Hong Kong's towering skyline conceals a rich trove of minerals, including iron, lead, silver, and tungsten, each contributing to Hong Kong's mining history. This geological heritage traces back to the 1860s with the discovery of lead in the Lin Ma Hang area. Over time, this resource faced various challenges, from wartime disruptions and labour disputes to typhoon damages and fluctuating lead prices. By 1958, mining operations ceased with 60% of reserves depleted.

The Ma On Shan Iron Mine, the largest in Hong Kong, operated from 1906 to 1976. During its 1960s peak, it produced 200,000 to 400,000 tonnes of iron annually, mainly exported to Japan. However, oil crises, reduced iron and steel demand, and competition from Australian mines led to the mine's 1976 closure.

Although commercial mining is absent today, sites like Silvermine Bay and Lead Mine Pass offer glimpses into Hong Kong's mining past. The history of the Silver Mine in Silver Mine Bay on Lantau Island dates back to the Qing Dynasty, with small-scale excavations already in progress. Large-scale operations started in 1886 when Hong Kong entrepreneur Ho Amei 何獻墀 introduced modern technology. A sprawling aerial ropeway transported mined ore to a coastal silver-refining factory. However, due to the poor quality of silver ore, production stopped in 1896. Despite its short lifespan, the mining legacy remains in the names of Pak Ngan Heung 白銀鄉 (White Silver Village), Silver Mine Cave 銀礦洞, and Silver Mine Bay 銀礦灣 in the area.

The entrepreneurial (and dandy) Ho Amei (source: Gwulo)

The former silver mine in Mui Wo (source: Tripadvisor)

The mysterious lead mine (source: Basel Mission Archive)

Lead Mine Pass 鉛礦坳 which connects Kowloon and the New Territories, carries a certain sense of mystery. It first made its appearance on a map from 1866 and is thought to have ceased operations around 1892. This cessation is suggested in a report on the New Territories' geology by Robert Daly Ormsby, who was the Director of Public Works in Hong Kong at the time. Information about the lead mine might be sparse, but its operation during a crucial era in Hong Kong's history underscores its importance.

Further adding to the intrigue is Kwong Shan Tsuen 礦山村 (Mine Hill Village) in Tuen Mun. While the specific minerals mined remain unknown, the village's proximity to a known tungsten occurrence provides a valuable clue about the potential mining activities in the area.

Take a Look

Our exploration of Hong Kong's evolution through place names reveals a multifaceted history of fishing, salt production, quarrying, and mining. Explore the map below to see how these activities have shaped our city’s place names.

Next Up

Stay tuned for the next chapter in our exploration, where we uncover the enduring imprints etched across Hong Kong's landscape as it transformed into a bustling trading hub.