Foreign Influence

The‘Not-so-English’ English Street Names in HK and Their Origins

Where Are You Really From?

A cocktail in LKF on Halloween led to this all-too-familiar ‘exchange’:

‘Hey, what are you?

‘I’m English.’

‘...but where are you really from? You sound French.’

Only this time, this ‘exchange’ was with the D'Aguilar Street sign.

Although most English street names in Hong Kong are Cantonese transliterations, over 11% of the non-Cantonese transliterated names originated from other languages. They are mostly named after non-British foreigners and places outside the British realm. Where did these street names with anglicised words come from?

Melting Pot

As an entrepôt in the early colonial days, Hong Kong attracted opportunists from all walks of life. Between 1844 and 1897, Hong Kong's foreign population had increased more than 18-fold. These merchants, officials, and missionaries played an important role in shaping the city. With 25% of all the English-based street names in Hong Kong named after individuals, much of their legacies can still be seen in the city.

Portuguese: Pioneers of HK’s Suburbs

The story of Portuguese in Hong Kong goes back to the early Portuguese explorations in India, the Malay Peninsula, Japan and Macau. Many Portuguese in Hong Kong were descendants of the early seafarers in Macau. By 1897, more than half of the Portuguese population in Hong Kong had been born in the city.

Europeans but ‘different’: Excerpt from 1897 Hong Kong Census Report

The multilingual Portuguese community played a crucial part in acting as buffers between the British and Chinese during the early colonial period. The Portuguese were seen as different from other Europeans and were discriminated against by the British.

In one case, when Granville Sharp (not the British campaigner for the slave trade abolition) laid out how he wanted to bequeath the Matilda Hospital, he noted in his will that:

“…that different classes be provided for and that the hospital be reserved for British, American and European patients, with some very limited discretion for the directors, but excluding Chinese, Portuguese and Japanese.”

— Granville Sharp, Founder of the Matilda Hospital

Soares family: Julia, Emma, and Francisco Soares (Source: Macanese Library)

As the city developed, high rents on Hong Kong Island drove many Portuguese to move to Kowloon. By the 1920s, Tsim Sha Tsui was mostly a Portuguese area and many of Kowloon's earliest developers were Portuguese.

Francisco Paulo de Vasconcelos Soares developed the Kowloon suburb of Homantin in the mid-1920s. He named the streets in the area after his family (Soares Avenue 梭椏道), his wife (Emma Avenue 艷馬道) and his daughter (Julia Avenue 棗梨雅道), as well as in honour of World War I (Peace Avenue, Victory Avenue, and Liberty Avenue).

Hiding in this cluster is a tiny path called San Francisco Path (舊金山徑, ‘Old Golden Mountain Path’ in Chinese, the moniker of the California city). At first glance, the street may seem oddly named after an American city – did Mr. Soares see himself as a saint, and named the street after his namesake, ‘Francisco’? While that cannot be entirely ruled out, it is more likely to be a tribute to the oldest garden in Macau (S. Francisco Garden/加思欄花園/Jardim de S. Francisco) that his father helped design.

Other Portuguese-named streets include Braga Circuit (布力架街) and Rozario Street (老沙路街). If you fancy a better view, you could even hike up to Boa Vista (野豬徑), which means ‘good view’ in Portuguese (the Chinese name means Boar Path) in Tai Tam.

Happy corner: Family and other happy stuff

Boa Vista: Not a bad view (Photo credit: Drone & DSLR)

Indians: Keeping Things in Check

"The Swagger Regiment" — A group photo of soldiers of the Hong Kong Regiment circa 1892-1902 (Source: Wikipedia)

In the 1750s, the British East India Company began training and deploying mercenary soldiers from the Indian subcontinent for overseas military engagements. They fought in the First Opium War which led to the cessation of Hong Kong. By the time the British occupied Hong Kong in 1841 there were already around 2,700 soldiers from the Indian subcontinent based in Hong Kong.

About one-third of the garrison in Hong Kong during the first decade of colonial rule was from India. Many of them transferred to the police after retirement; prior to WWII, 60% of the police force were Sikhs from Punjab. Even though most of them ended their service in Hong Kong after India gained independence from Britain in 1947, traces of the community’s military involvement can be seen in some street names.

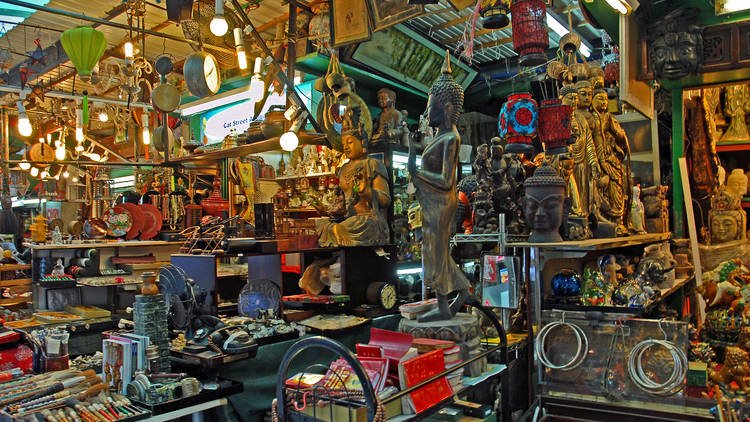

‘Lascar’ in Upper and Lower Lascar Row (摩羅上/下街) was used by the British to refer to seafarers from the Indian subcontinent and is derived from ‘lashkar’, the Persian word for a military camp. The area was home to dozens of Indian traders and in-between-jobs sailors from the 1840s to 1920s. Many of them brought products from all over the world to sell and the area became a marketplace for secondhand goods.

(photo credit: Timeout)

Jat’s Incline (扎山道) in Wong Tai Sin was built by the 119th Infantry (later renamed the 2nd Battalion of the 9th Jat Regiment) in 1907 and repaired in 1932 by the 3rd Battalion of the 9th Jat Regiment.

(photo credit: hhkk.info)

In addition to helping keep things in check, South Asians were among the first to ‘check Hong Kong out’. After the British took control of the New Territories in 1889, a team of Indian surveyors led by George Passman Tate, whom Tate’s Cairn (大老山) is named after, conducted a large-scale survey of the area.

It is no coincidence that some of the largest river systems in the New Territories were named after major rivers in India and Pakistan – River Indus, River Jhelum, River Chenab, River Sutlej, River Beas, and River Ganges. Although these rivers have been renamed after the Handover, it is still fascinating to think that four of five Punjab rivers were in Hong Kong at one point.

Punjab in HK — 1945 map showing the area around Sheung Shui (Source: National Library of Australia)

Jews: Philanthropists, a Governor & a Camel

The first Jewish settlers in Hong Kong were descendants of Jews who fled the Inquisition to Baghdad. During the 19th century, they travelled to India to set up trading operations, and later to Canton, Macau and Hong Kong.

Funded by the Sassoons — Asia’s largest Jewish cemetery (Source: Jewish Historical Society of Hong Kong)

While Jews never constituted a large community in Hong Kong, many influential Jews have left their mark in the city, including Sassoon Road (沙宣道) and Kadoorie Avenue (嘉道理道) named after the two powerful Jewish families. In addition to founding the China Light and Power Company (CLP Group) and The Peninsula Hotels, the Kadoories engaged in many philanthropic endeavours including housing Jewish refugees in-transit after WWII. Kadoorie’s philosophy “help people to help themselves” was evident in the often neglected New Territories in the colonial days. The family set up Kadoorie Farm and Botanical Garden, originally intended to be an experimental farm to help poor farmers. In Yim Tin Tsai, Sai Kung, they donated cement and pipes to villages to facilitate freshwater access.

Matthew Nathan, the 13th and only Jewish governor of Hong Kong, catalysed the development of Kowloon by constructing what would eventually become Nathan Road (彌敦道) in the then-marshy area. The eccentric Emanuel Belilios, who funded the first government school for girls in Hong Kong famously kept a camel on the Peak which sadly fell off a cliff.

Parsis: Small but Mighty

Light it Up — Parsee Illuminations at Lyndhurst Terrace celebrating the visit of H.R.H. The Duke of Edinburgh in 1869 (Source: University of Bristol)

Parsis are descendants of Zoroastrian followers who fled to India from Persia (present-day Iran) to escape Muslim persecution 1,300 years ago. Some eventually settled in Hong Kong in the 19th century through trade.

As a small community, they contributed to the establishment of many century-old institutions, including HSBC, where two of the founding members were Parsis, the Star Ferry, founded by Dorabjee Naorojee Mithaiwala, and Hong Kong Ruttonjee Sanatorium, funded by Jehangir Hormujee Ruttonjee.

Hormusjee Naorojee Mody, whom Mody Road (麼地道) was named after, was a businessman and land developer. He alone contributed $285,000 to the establishment of the University of Hong Kong. As the first major benefactor to pledge $150,000 to construct the Main Building, he set the precedent for others to follow. He also contributed to the founding of the Hong Kong Jockey Club and Kowloon Cricket Club.

In addition to Freddie Mercury, Robert Kotewall, a businessman and civil servant born to a Chinese mother and a Parsi father, is another Parsi showbiz connection. He wrote “Uncle Kim” (鑒叔), the first English Cantonese opera in 1921 and successfully petitioned the Governor to allow the cast of both genders in Cantonese operas in 1933. Despite his fall from grace with his involvement in aiding the Japanese army during the Japanese occupation, his legacy continues. He left behind Kotewall Road (旭龢道) and a great-grandson who continued his love of the arts by starring in Hollywood productions such as The Social Network and The Handmaid’s Tale.

Heavy losses — Cromlech honouring Wales’ fallen in WWI near Pilckem, Belgium (Source: BBC)

Minden Avenue (棉登徑), Minden Row (緬甸臺), and Blenheim Avenue (白蘭軒道) near Signal Hill in Tsim Sha Tsui are named after the two Royal Navy ships HMS Minden and HMS Blenheim, which took their names from German battlefield towns. The German connection is lost in Minden Row particularly as its Chinese name was mis-transliterated to the Chinese name of Myanmar「緬甸」(min5 din1).

Further up in Yau Ma Tei, Waterloo Road (窩打老道) and Pilkem Street (庇利金街) bear the names of two Belgian towns where the Battle of Waterloo and Battle of Pilckem Ridge took place. At the start of World War I in 1917, Pilckem Ridge in Ypres, Belgium, was heavily contested in the Battle of Passchendaele. Over 30,000 British troops lost their lives in this battle.

Fanciful

France in LA in HK — Boulevard du Lac, part of The Beverly Hills development in Tai Po (Source: Wikipedia)

Aside from remembering the fallen, foreign places are also used to market property developments. Thanks to Eurocentrism, luxury properties in Hong Kong have been given vaguely western names for the past two decades to sound more ‘upscale’.

In the New Territories, you can find clusters of streets named after California cities, Swiss Alps, and French wines as a result of these property developments.

San Simeon Avenue (西蒙徑) – Spanish

Zermatt Avenue (策馬特大道) – German

Lafite Avenue (洛菲大道) – French

However, having a fancy voice doesn't necessarily imply knowledge. 'Viale', for example, is used as a suffix, as opposed to a prefix, as it should be in Italian street names.

Hong Kong English

Words from other cultures have been adapted into our day-to-day vocabulary by the city over the years, and some can be seen in our street names.

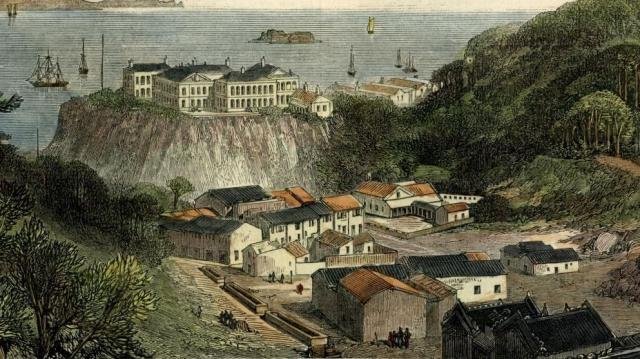

Beach view looking onto Praia Grande: “Veranda of Nathan Kinsman’s residence in Macau,” ca. 1843 (Source: MIT Visualizing Cultures)

Praya: From Macau With Love

The term ‘Praya’ was borrowed from our neighbour Macau. Derived from the Portuguese word for beach 'Praia', it refers to a seafront promenade dotted with houses. The crescent-shaped Praya Grande beach in Macau was the Portuguese colony's most famous view and appeared in many artworks. The term was transplanted when the British set up their own Praya in Hong Kong.

The Praya in Hong Kong was once part of Hong Kong Island's original seafront. After the Praya Reclamation Scheme in the late 19th century, the Praya became Des Voeux Road (德輔道), Johnston Road (莊士敦道) and Hennessy Road (軒尼詩道). It is still possible to see remnants of the original Praya in Kennedy Town (Praya, Kennedy Town 堅彌地城海旁), but with reclamation it has become landlocked. Even though the Praya is long gone, there are a few streets that still retain ‘Praya’ in the name.

View of the Praya in Hong Kong, taken estimated in 1868 (Source: University of Bristol)

Excerpt from the 1874 Reclamation Plan (Source)

Interestingly, not all seafront promenades in Hong Kong are referred to as 'Praya'.

Other terms such as 'promenade' and 'Hoi Pong', the Cantonese transliteration of promenade「海旁」are also used. There seems to be no logic in the manner in which 'promenade' is used. Lei Yue Mun Praya, in particular, begins its linguistic journey on Lei Yue Mun Praya Road (鯉魚門海傍道) and ends on Lei Yue Mun Hoi Pong Road East (鯉魚門海傍道東).

Nullah: From Valley Stream to Concrete Drainage

Seamen's Hospital at hospital hill in Wanchai in 1873, the nullah that would become Stone Nullah Lane can be seen at the bottom of the painting (Source: Gwulo)

The word ‘Nullah’ was documented in English as far back as the mid-17th century in the writings of British merchants and officers in India. It refers to ‘a stream in a narrow valley, a drain for floodwater’ and has roots from Bengali নালা (nala), Hindi नाला (nālā), and Sanskrit नाडी (nāḍī). The term was later brought to Hong Kong to describe open-air, concrete-lined channels for diverting flood waters.

Although some nullahs still exist, many have been covered up through the years. Stone Nullah Lane (石水渠街) in Wan Chai and Nullah Road (水渠道) in Mong Kok are remnants of their watery past.

English or…?

As a largely homogeneous society with over 91% of the population being Chinese, Hong Kong has long been home to an eclectic mix of people and cultures fueled by trade. Though Hong Kong was once a British colony, the linguistic diversity in its street names reflects the diverse communities that helped build the city. Don't assume an English street sign is really ‘English’ the next time you pass one.

In case you're still wondering about Mr. D'Aguilar, despite the name being derived from Old French, he was a Liverpool native. The ghost of D'Aguilar was right — he was English after all.

Explore the interactive map below to see the linguistic roots of their ‘English’ street names:

An edited version of this article originally appeared on Hong Kong Free Press.